Previous | Next

New polls:

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Saturday Q&A

Some weeks, we can guess what subjects will attract a lot of questions. Some weeks, not so much. This week was one of the latter; while it's not necessarily surprising we got dozens of questions about gerrymandering, it's also not what we would have predicted.

Current Events

S.S. in West Hollywood, CA, asks: You've mentioned several times that there's a significant degree of uncertainty in the science of gerrymandering these days because of the distortion Donald Trump has created in past electorates by being on the ballot (will voter demographics more closely resemble 2020 or 2018?). Is that no longer thought to be an issue, or is it merely that the Trump effect isn't big enough to cause any doubt in these Republican majorities in state legislatures?

V & Z answer: It's still a dynamic that could come back to haunt the gerrymanderers. Some states (e.g., Florida) played things more carefully, while others (e.g., Texas and Ohio) were more aggressive. If the post-Trump electorate isn't as red as the latter states are expecting, they could get burned in some districts. Texas, in particular, also has the problem of demographic change. Not only is the Democratic-leaning population of the state growing, but the decline of the petroleum economy could cause some of the Republican-leaning population to decamp elsewhere in search of better economic prospects.

B.R. in Lake Oswego, OR, asks: Once the Republicans have gerrymandered their states, it seems unlikely that the Democrats would ever be able gain majorities to "undo" the political maps that have been created (or vice-versa in blue gerrymandered states). If the underlying premise of creating districts (state legislature or congressional districts) is "fairness" and "just proportionment with respect to representation," once one party establishes districts to its favor, how can the fairness ever be obtained, given that racial and political gerrymandering is unfair by definition?

V & Z answer: There are three ways in which some or all gerrymanders might be broken. The first, and most likely to happen in the short term, is that the courts step in and toss out problematic maps. The second is that Congress passes some sort of legislation that limits or eliminates gerrymanders. And the third is that there are population shifts over the course of the next decade. That's the slowest of the three possibilities, but also the most certain. Since the last round of map-drawing, there are at least a dozen districts that have shifted 10 points or more in favor of the Democrats, and slightly fewer than a dozen that have shifted 10 points or more in favor of the Republicans.

S.K. in Sunnyvale, CA, asks: The Democrats don't have the gastrointestinal fortitude for it, but hypothetically, if California, Colorado, etc. were to rescind their independent redistricting committees and gerrymander the heck out of their states, how much would it help? Could they all but guarantee a Democratic house? If so, would that plausibly be enough to get Senate Republicans to agree to a federal anti-gerrymandering law?

V & Z answer: No. The three large (or large-ish) blue states that use nonpartisan redistricting commissions are California and Colorado (as you note) and Washington. The current delegations from those states, in order, are 42D/11R, 6D/3R, and 9D/3R. Even if those states could someone create 100% Democratic delegations, we're talking a net gain of 17 Democratic seats (California is losing one, but Colorado is gaining one). That's about the number that the Republicans are gaining from Texas and Ohio alone, and that's before we talk about Florida, North Carolina, Georgia, Arizona, etc.

M.C. in Oak Ridge, TN, asks: In redistricting, how to objectively distinguish between the relatively fair boundaries that good-hearted folks might draw, and obvious partisan perversions of such? Concepts like the efficiency gap come up against non-homogeneous natural and political geography, and non-partisan appointments are often such in name only. (Un)fortunately, there is so much room for improvement that the perfect need not be the enemy of the good. Have we any proposals for rules that could be easily accepted and effectively wielded in the real world to prevent heavily gerrymandered maps?

V & Z answer: This is one of those situations where we might make use of (an adapted version of) Associate Justice Potter Stewart's famous observation about pornography: "I can't define a gerrymandered district, but I know one when I see one."

There are a few pretty obvious indications of a gerrymander that, taken in aggregate, allow one to reach a pretty firm conclusion. To start, a map should "crack" (divide up) polities as little as is possible. Neighborhoods, cities, and counties should not span multiple districts unless those neighborhoods, cities, and counties are very large. Similarly, there is relatively little non-gerrymandering justification for complicated and crooked boundary lines and districts that are oddly shaped (particularly if they are oddly shaped on all sides). There is also relatively little non-gerrymandering justification for having districts whose sizes differ significantly.

The efficiency gap (EG)—a measurement of "wasted votes," and whether one party's votes are being disproportionately wasted statewide—is also a useful tool. It is true that the original formulation of EG was flawed, in that it did not account well for states that are unbalanced in favor of one party or the other. However, Corrected Efficiency Gap appears to fix that issue.

M.B. in New Orleans, LA, asks: My (very conservative) father recently sent out a group text to our family about his Medicare Part A no longer being free. He said it was because "the hidden taxes to pay for all the spending is in effect" (i.e., the Democrats did it to pay for the infrastructure bill). To him it makes perfect sense what is going on, but I am skeptical for two reasons:

- This is way too soon to already be seeing implementation of something passed so recently.

- I doubt the "Medicare for All" party were the ones to cut Medicare.

However, at this point, both my father and I are just speculating from our own points of view. So, in the event I cannot escape discussion about it, I'm hoping you might be knowledgeable about exactly why his previously free Medicare Part A now requires a premium. Who is responsible for the change, and which bill or process made it happen?

I realize this is might not be a typical question, but it is indeed very much political.V & Z answer: We have only partial information about your father's thinking here. In particular, it's not clear if he thinks that Medicare costs were directly increased by the infrastructure bills, or if he's talking about an indirect effect, along the lines of "any increase in outlays is inherently connected to any increase in levies." The talk of "hidden taxes" seems to suggest the latter.

In any case, we can tell you three things. The first is that about 1% of Americans have to pay for Medicare Part A. That requirement is based on the work history of a person and their spouse; less than 40 quarters in the workforce means you have to pay up. That means it's possible to go from "paying" to "not paying," if a person (or their spouse) happens to work the additional quarters needed to get to 40. However, there isn't a way to go from "not paying" to "paying" that we are aware of. And, in any event, there hasn't been a change from 2021 to 2022, excepting that premiums (for those who do pay) have gone up, from $252/month to $274/month, and the deductible has increased from $1,484 in 2021 to $1,556 in 2022. However, this has nothing to do with the Biden administration; Medicare costs go up every year, as you might expect, based on a formula adopted by Congress. The increases this year are the largest in history, but this year's Social Security cost-of-living adjustments are also historically large.

Second, you are right to think there hasn't been time for the bipartisan infrastructure bill to kick in yet. And even if there had been time, that bill is not funded by taxes on private citizens; it's funded by borrowing, taxes on certain businesses, and some bookkeeping magic. The only aspect of Medicare that is addressed in the bill is a Trump-era plan to change the way rebates work when pharmaceutical companies sell drugs to the government. This is a very complicated issue, which you can read about here if you really want to get into the nuts and bolts. However, it was set up to create the impression of lower drug prices, but at the expense of higher Medicare premiums. Ultimately, it's estimated that the policy would have cost the federal government about $200 billion in the next decade. Anyhow, the bipartisan bill suspended implementation of the plan until at least 2023 in order to save some money (see "bookkeeping magic") and to give time for a full review of the cost-benefit analysis. The fact that the pharmaceutical industry is hopping mad about the (temporary?) suspension is probably instructive. Whatever happens, since the policy has not yet been implemented, its suspension has not had an effect on drug costs.

Third, and finally, the reconciliation bill hasn't been passed yet, so it could not possibly have affected Medicare premium prices. If and when it is passed, it actually has a bunch of goodies for Medicare recipients, like hearing coverage. It most certainly does not increase Medicare Part A premiums, which—as you point out—would not be the sort of thing a Democratic Congress and president would do.

In short, your father is either pulling things out of thin air, or his understanding has been garbled in the way that right-wing media often garble things in order to make Democrats look bad. If nothing else, note that the AARP has published an article talking about how great the bipartisan bill is for seniors, and another article talking about how great the reconciliation bill is going to be for seniors on Medicare. If the bills were jacking up Medicare prices, AARP wouldn't be writing articles like that.

G.H. in Chicago, IL, asks: How did Wisconsin's "stand-your-ground" law apply in the Kyle Rittenhouse case? In the video I've seen, Rittenhouse was fleeing from Joseph Rosenbaum across a parking lot and didn't shoot until Rosenbaum caught up to him. He was again fleeing in the direction of the police when he was knocked down from behind, kicked by one pursuer, hit with a skateboard by another and then had a gun pointed at him by yet another. He was on his back. Is it your view that he didn't retreat well enough to satisfy the retreat requirement in a "retreat" state? Or do you have the idea that you have no further recourse in a retreat state after retreating fails?

Eric Zorn, a former Chicago Tribune columnist, warned a year ago that, based on his review of the video evidence, Rittenhouse was undoubtedly terrified and likely to "walk." Zorn is by no means conservative or an advocate of open-carry laws, nor am I.V & Z answer: Let's start with a reminder of what we actually wrote:

As to the more serious charges, Rittenhouse's lawyers were able to make the case that he was acting in self-defense. It used to be the case that, if a person was faced with danger and was outside of their residence, they had a duty to try to retreat and could not invoke self-defense if they did not make an attempt to do so. Recently, as encouraged by the NRA and other lobbyists, and by the advent of "stand your ground" laws, a person can claim self-defense in any circumstance as long as they felt they were in danger and as long as they were not the aggressor.So, we did not claim that Rittenhouse invoked "stand your ground" laws, we claimed that there has been a philosophical shift in the United States, and that "stand your ground" is a part of that.

We stand by that point. When the law of (most of) the land is "duty to retreat," then guns (or other weapons) are only to be used as a solution of last resort. This is a very defensive-oriented way of thinking about things. On the other hand, when the law of (most of) the land is "stand your ground," then weapons become appropriate (or, at very least, legal) in a much wider variety of circumstances. This is a much more offensive-oriented way of thinking about things.

Let's put it this way: If Rittenhouse had charged into the middle of a situation where he did not belong, armed with an AR-15 (or similar weapon), 50 years ago, he would have been taking a vastly greater legal risk than he took when he did so in August of last year.

Politics

P.M. in Palm Springs, CA, asks: You wrote about the malpractice of Politico, with its propagandistic article on the poll that had Donald Trump outpacing Joe Biden in five swing states. The other political site I go to every morning, besides E-V.com, is Taegan Goddard's Political Wire. Commenters on that site continually bash Politico for its right-leaning tendencies and/or its obnoxious both-siderism. Has Politico changed over the years? Has its new German owner or controller taken it somewhere less reliable?

V & Z answer: That piece we wrote up was pretty bad, and it's definitely going to cause us to keep a close eye on Politico to see if the quest for clicks, as prompted by their new German owners, leads to a shift in coverage. That said, every outlet has a clunker once in a while, and even that piece might have been salvaged with better writing. And while Politico is sometimes clickbait-y, and sometimes goes too far in service of both-siderism, and occasionally prints some pretty lousy op-eds (ahem, pretty much everything by Rich Lowry), we aren't concerned yet. Certainly, The Hill is more problematic than Politico is, at least at the moment.

The other outlet that's been disappointing recently is The Washington Post. They have plenty of good coverage, to be sure. But they are worse on the both-sides front than Politico is, and some of their opinion columnists are absolutely embarrassing. We are thinking, in particular, about Marc Thiessen. Here are the headlines for his last eight pieces (he writes two per week):

- Three cheers for 'Let's Go Brandon'

- It's hard to mess up being vice president. But Kamala Harris has.

- The Democratic Party's progressive wing is on a kamikaze mission

- The danger of critical race theory

- Democrats are lying about critical race theory

- Climate change is not an 'existential threat'

- The Biden administration's self-inflicted school board disaster

- Biden wants you to believe shortages and inflation are another 'extraordinary success'

When (Z) worked for The Daily Bruin at UCLA, opinion columnists were given wide latitude to express their views, but their columns were also vetoed if they were just angry partisan screeds with no meaningful argument. Thiessen's pieces are pure Republican propaganda; they could easily be Trump campaign commercials. It's not clear to us if the Post exercises any veto power at all over their op-ed columnists, but the only purpose of these knee-jerk, reactionary pieces that offer no actual insight into the issues seems to be to allow the Post to say "See? We give space to Republicans, too!" If they cut Thiessen loose and keep George Will, though, they can still say that without facilitating a propagandist twice a week. At least Will has something interesting and/or thought-provoking to say, much of the time.

L.O-R. in San Francisco, CA, asks: Regarding "Can A Gay White Man Beat a Straight Black Woman?", why is Kamala Harris repeatedly described as Black, but never as Asian (or, more relevantly, South Asian)? It appears to be that you're following the implicit racism of the USA, that one bit of Blackness makes one all Black and every other identify is obscured. In fact, Harris is deeply connected to the Asian community—especially the South Asian community—and would attract some significant number of voters on that characteristic. I understand that she herself often defaults to identifying as Black for shorthand, but it seems that an article highlighting her gender and race should talk about all of her. Can you explain your reasoning for not doing so?

V & Z answer: The point of our piece was that "gay," "white man," "woman," and "Black" are all identities whose plus-minus, politically, have changed a lot in the past couple of generations. And we were wondering which combination might potentially be the stronger one in 2024.

It is true that Harris is part South Asian and that she regards that as an important part of her identity. But there's no chance it will be as significant to her political prospects as her gender and her Black heritage, both in terms of some of the people who might choose to vote for her (if she runs) and some of the people who might choose to vote against her.

R.M.S. in Lebanon, CT, asks: Can either of you explain the rationale behind the Squad's "nay" votes on the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act? It seems like they don't support the bill because they don't think the plan provides enough funding for other needs, but this makes no sense to me. Certainly, $1.2 trillion in new infrastructure funding is better than $0 in new infrastructure funding. Even Rep. Nicole Malliotakis (R-NY), New York City's sole Republican in Congress, supported it, saying her state and city badly need the additional funds.

The more I see the Squad in action, the more frustrated I am with them. All-or-nothing approaches are never a good way to govern a country. This country is very diverse culturally and geographically, and it is impossible for anyone to get everything they want in legislation.V & Z answer: We would start by pointing out that there is a world of difference between a protest "nay" vote and a decisive "nay" vote. The latter, which are the sort that Sens. Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) are threatening to cast, are more consequential by several orders of magnitude than the former. As we pointed out a couple of times, there is no question that both Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and the members of The Squad knew those votes would not be needed, and that they voted "nay" with the blessing of the Speaker.

So, why would they feel the need to make a statement like that? Well, just as a great many Republican members are concerned only about a primary challenge from the right, the members of The Squad are concerned only about a primary challenge from the left. The last thing that, say, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) needs is to have to run against a Jill Stein clone who blasts the representative as a "phony" Democratic socialist who lines up with the "corporate" Democrats every time it comes time for the House to vote. A high-profile "nay" vote like this one allows AOC to maintain her rabble-rouser bona fides.

M.M. in La Crosse, WI, asks: I have just one question about Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX). How the hell does this clown keep getting re-elected? Are his constituents really that stupid? Ok, that was two questions.

V & Z answer: Shortly before writing this answer, (Z) did an escape room titled "The Mystery Of Senator Payne," which was about a much-hated U.S. Senator named Bill Payne who is revealed, over the course of the puzzle-solving, to also be a Satan worshiper. After (Z)'s team successfully escaped, (Z) wondered why they didn't just cut to the chase and call it "The Mystery of Senator Cruz." The management said that, because of defamation laws, they had no comment in response to that question.

Anyhow, Cruz has learned the same lesson that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has. To win elections, you don't need to be the best major-party option, you just have to be the least-bad major-party option. And in Texas, where no Democrat has won statewide election since 1994, any person with an (R) next to their name is automatically less bad than any person with a (D) next to theirs. The Democratic nominee could be Jesus, Santa Claus, Davy Crockett, Clint Eastwood, or Donald Trump Jr. and it apparently wouldn't matter. This is what would-be Texas governor Beto O'Rourke (D) will be up against next year.

Civics

C.C. in Dresden, Germany, asks: This week, you once again wrote about Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin and their reluctance to kill the filibuster.

My question to you is: Isn't it high time to devise a new constitution and use the opportunity to fix all the broken things in the system (filibuster, gerrymandering, voting rights, Congressional oversight etc.)? What would be a way to start this, what say would the states have in this, and what would be the chances of succeeding with this?

Also, would it ultimately be a possibility to allow states who are not interested in this to remain the U.S., while the other part would form the New United States of America or something?V & Z answer: Here is the text of Article V of the Constitution:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress; provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article; and that no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.In plain English, if two-thirds of the states want a constitutional convention, Congress has to call one. It is likely also the case that Congress can call a convention of its own volition. That convention would come up with amendments to the Constitution that would theoretically have to be approved by three-quarters of the states (though Congress can change the rules for approval, if it wishes).

That is how it would work in theory. In practice, it's not going to happen. European countries tend to be pretty comfortable with change, including changes to their governing documents. They are also pretty comfortable with throwing out constitutions and starting fresh. Americans, by contrast, are much more resistant to change, and have a tendency to fetishize the U.S. Constitution. A constitutional convention would be too radical for most Americans' tastes.

Beyond that, the folks who would theoretically call such a convention—state/federal politicians—are well aware they would be playing with fire. Article V is pretty vague, and gives the states, the Congress, the courts, the executive branch, etc. zero power over the proceedings once the convention has been called. Yes, three-quarters of the states would ostensibly have to approve the resulting constitutional amendments proposed, but not so fast. There's only been one constitutional convention in U.S. history, and that one ignored all the rules (and all the instructions given to them by state legislatures) and did what it wanted to do. If a new constitutional convention were to write a new Bill of Rights, or a whole new Constitution, and to declare that ratification only requires a majority of states, that might stick. The convention would have precedent on its side, and if a majority of states agree to accept its work, what option do the remaining states have but to go along?

There is currently no legal way for states to leave the union. The only way that changes is if the hypothetical constitutional convention creates an exit clause in the new constitution.

M.D. in San Tan Valley, AZ, asks: I was curious to hear the news recently of VP Kamala Harris taking over as "Acting President" for 85 minutes while President Biden was under anesthesia for his colonoscopy. What I was wondering is: How was Harris addressed during that time period? Would she still be addressed as Madam Vice President, or is she addressed as Madam President during the time she is the acting president?

To add an extra component to this question if you don't mind, after Secretary of Defense Mark Esper was fired under the Trump administration, he was replaced by Christopher Miller who became the acting Secretary for the remainder of Trump's term. If he were to do an interview for a news station or news show today, would he be addressed as "Mr. Secretary" or simply Mr. Miller, due to never actually being confirmed as a Secretary of a Presidential administration cabinet?V & Z answer: Although the term "acting" is used in both cases, they actually mean rather different things. In Harris' case, the assumption of powers was temporary by design. She did not occupy the office of president, nor was there an expectation that she was likely to occupy the office in the near term. She was VP before, during, and after the colonoscopy, and so was addressed as Madam Vice President during her 85 minutes in the big chair.

By contrast, an acting cabinet secretary is "acting" because they are waiting to become a full-fledged cabinet secretary. That does not entitle them to the use of their (potential) future title, as an acting secretary is not a secretary. So, for his entire time in office (since he was never confirmed), Miller was properly addressed as Mr. Miller. However, because he had been nominated to high executive office by the President of the United States, he was entitled to be referred to as "Honorable" in official announcements, correspondence, etc.

History

P.S. in Brooklyn, NY, asks: A few years back I saw this Vice News story on the origins of Thanksgiving as a holiday, and the work of Sarah Josepha Hale to establish such a holiday. From this angle, Thanksgiving seems almost progressive.

Thanksgiving has been one of my favorite holidays (probably because it often lands on my birthday, as it does this year) and was hoping you folks could shed some more light on this history as I think more folks should know.V & Z answer: First of all, Happy (belated) Birthday!

Second, there are four key players in establishing Thanksgiving as an American holiday:

- George Washington was the first president to declare a Thanksgiving holiday (Thursday, Nov. 26, 1789), though he did not envision it as an annual occurrence.

- Hale became the foremost promoter of Thanksgiving as an annual holiday, starting with a chapter in her 1827 book Northwood: A Tale of New England, and continuing in the pages of Godey's Lady's Book, for which she served as editor for 40 years.

- Abraham Lincoln established Thanksgiving as an annual holiday in 1863. He did so via presidential proclamation, and so did not formally make it a holiday, but it was nonetheless celebrated every year from then on.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the legislation making Thanksgiving a national holiday, and setting it to be commemorated on the fourth Thursday of November. For a couple of years, he tried to make it the third Thursday in November, so as to extend the economy-boosting holiday shopping season. However, most Americans rebelled against "Franksgiving."

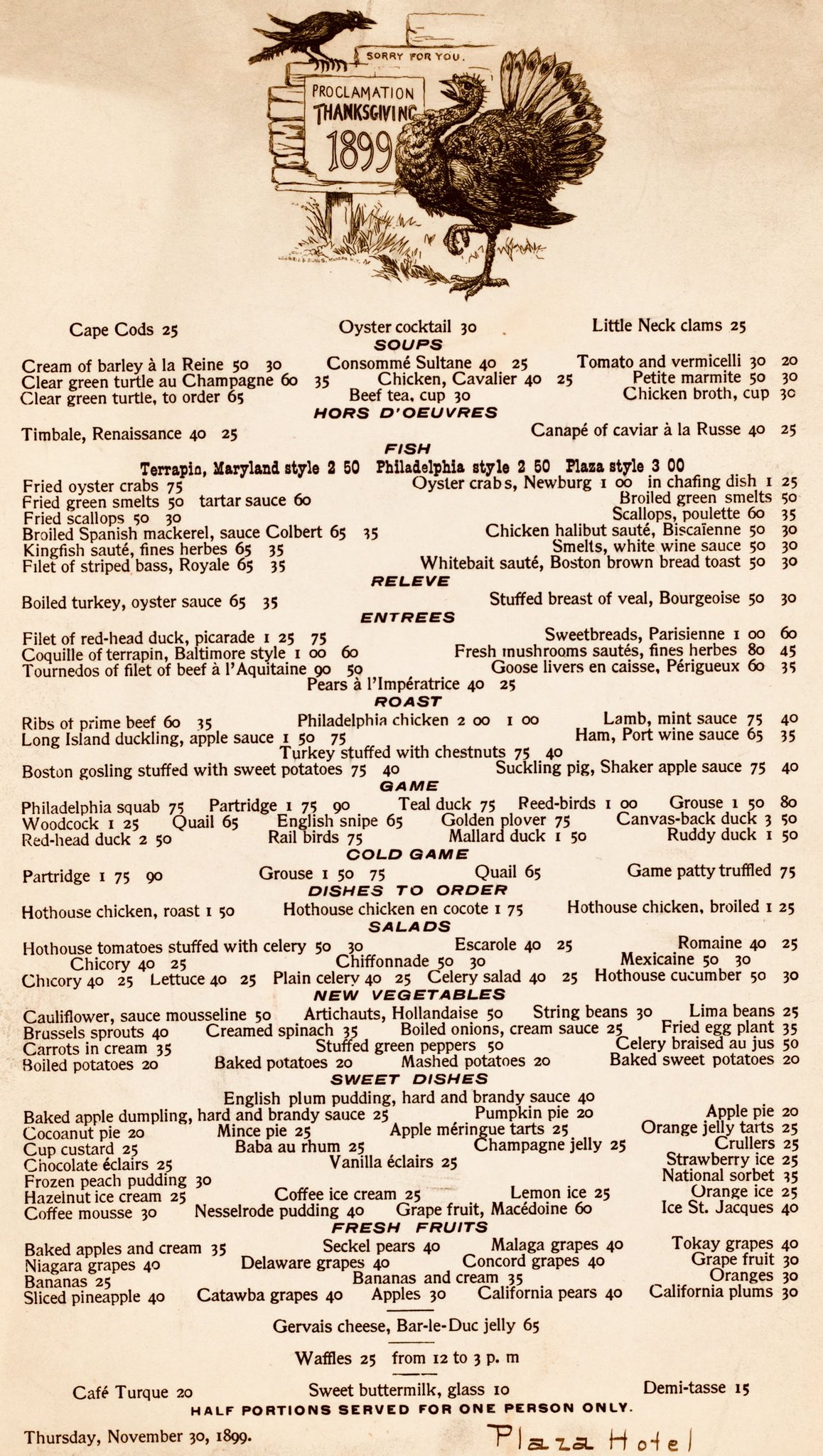

It's not clear exactly how much Hale influenced Lincoln, but there was certainly some influence there. That said, they both envisioned the holiday as being much more of a religious occasion than it ultimately became. This 1899 Thanksgiving menu from the Plaza Hotel in New York makes clear that heavy-duty eating, particularly of turkey, had become the focus of the holiday by the turn of the 20th century:

Z.Z. in Coarsegold, CA, asks: Back when the Internet, as we know it today, was starting up I remember reading an article on gun control laws before the Civil War and gun control laws after the Civil War. Of what I can remember of the article, there are significant differences. Are there any books or research articles on this subject?

V & Z answer: The big difference is that Black people stopped being slaves and started being citizens, and white people didn't want Black people to have guns. So, white legislatures, particularly in the South, started requiring gun permits or outlawing low-cost guns as means of keeping guns out of the hands of Black folks.

There is a lot of literature on this, but much of it is hyperpartisan crap. Armed in America: A History of Gun Rights from Colonial Militias to Concealed Carry by Patrick J. Charles and Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America by Adam Winkler both play it down the middle, though.

P.Y. in Upper Nyack, NY, asks: I thank you for addressing my question. However, I think you are taking the Moses "ghetto" quotes wrong.

I believe in those quotes he is referring to his work with NYCHA in clearing tenements and building (better, in his mind) public housing. The NYCHA work was generally positively received in its day when Jacob Riis' How the Other Half Lives was still on people's minds.

I have been googling my tail off and even looking at old census data, and I am pretty sure Moses didn't run any highways through Black neighborhoods. Now, I get that he displaced (V)—but, then again, (V) isn't Black; he's Jewish, and guys like Moses, born in the 1880s, are known to have used the term "ghetto" to refer to Irish, Italian and Jewish immigrant neighborhoods.

I don't want to beat a dead horse, nor to "stand up" for Moses, but I think the idea that Moses built highways through Black neighborhoods is ahistorical and that while most people would let this pass, (Z) would probably be a bit of a stickler for getting it straight before the page is turned ... it is very relevant to today's politics.V & Z answer: Did Moses build a highway through a Black neighborhood? Probably not. Did he displace Black citizens in the execution of his projects? Almost certainly. The distinction here seems pretty small to us, particularly to (Z). If people lose their homes and are displaced, they don't really care if it's to build a highway or a public park or public housing.

Answering this definitively would require research that cannot be done on the Internet. In addition to census data from the early 20th century, it would be necessary to go through Moses' personal papers, which are held (mostly) at the New York Public Library, and are not online (except for a very general finding guide).

But even without that research, we have a pretty strong basis for our assertion that Black people were displaced. First, even if they were only 1-2% of the population, it is improbable that other poor communities would be displaced, but they would be untouched. Second, it's true that "ghetto" was used by people of Moses' generation to refer to all manner of low-income communities, regardless of the predominant ethnicity. But, as we wrote, it had taken on connotations of "poor Black community" by the time Moses wrote the essay we quoted. Further, Moses' essay was specifically in response to claims that his work was done in service of antiblack racist goals. And his response was "The bridge thing is not true, and good luck replacing ghettoes without displacing some people." It is implied, given the main thesis of his essay, that he was referring to displacing Black people.

D.L-O. in North Canaan, CT, asks: Thanks for the exposition on archetypes in response to the question from T.J.R. in Metuchen. I am, however, somewhat puzzled by the predominant answer to the "She was a great American" category. No disrespect to either Betsy Ross or Rosa Parks, but my answer to this question would be somewhat different. I have several options and I'm not sure which I would end up with. Both Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton deserve the title "Great American." Another possible choice would be Margaret Sanger.

I wonder why these women are overlooked, especially since voting rights and pro-choice issues are at the forefront for many of us. Do you think it might be because Betsy Ross and Rosa Parks have easier names to remember?V & Z answer: Well, as we noted, this process is somewhat mysterious. However, a big part of it, particularly in this case, is the material taught in history courses (especially pre-collegiate history courses). There's only room to talk about so many people, even if you have a whole year to teach the subject, before it becomes too much for students to absorb. Once you've dealt with the folks who simply must be dealt with (Christopher Columbus, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, etc.), there aren't that many slots left to focus on important women. Those women who get substantive attention tend to check multiple boxes (they are both a woman and a member of a minority group) or they tend to have particularly engaging stories, or both.

Students used to hear a lot about Betsy Ross because she was "the" woman of her generation. Once it became clear that the "making the first flag" story was partly or wholly false, she faded quite a bit. Today, the three women who are far and away most likely to be named in response to that prompt are Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, and Pocahontas. All three check multiple boxes, and all three have stories that make for compelling lectures for students.

There are plenty of women who are just as important, and perhaps more so, that just don't get substantively covered in a lot of history courses—the three you name, Jane Addams, Eleanor Roosevelt, Ida B. Wells, Margaret Chase Smith, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mercy Otis Warren, etc.

Gallimaufry

F.L. in Denton, TX, asks: Some time ago (and I'm talking years), you presented more than a few examples of terms that were originally pejorative, racist, sexist, or ethnic slurs, yet, even in today's very 'woke' society, they are considered acceptable for use. The only example I can remember is "Paddy wagon," which might be construed as a slur of the Irish. Could you provide a link to that article or reproduce it here?

V & Z answer: Here you go, though we didn't actually include "paddy wagon" in that item. Note also that the words are largely "acceptable" because people are unaware of the origins of the words/phrases. It's usually not the case that they are aware but just don't care.

C.P. in Silver Spring, MD, asks: I was reading a biography on George Lucas recently and was surprised to learn he graduated from none other than USC. Given that the E-V.com staff writers have long described USC as a wretched hive of scum and villainy, any comment as to how one of its graduates created such a memorable film franchise?

V & Z answer: If you want to build a good film school, it helps an awful lot to be in close proximity to the entertainment industry and the resources that entails. There is a reason that UCLA, USC, and NYU are the three best film schools, and that nearly all of the top 10 (Columbia, AFI, Cal Arts, Cal State Long Beach, Chapman, etc.) are either in New York City or in the Los Angeles area.

It's a good thing that USC has a film school. In addition to the occasional lottery jackpot, like George Lucas or John Singleton or Robert Zemeckis, someone has to write all those softcore Cinemax movies and direct all those Hallmark Christmas films.

Previous | Next

Back to the main page