Previous | Next

New polls:

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Saturday Q&A

We hope you like long answers, because there are a couple of those today.

Current Events

J.G. in New York, NY, asks: Let's say it's Election Day 2024. Jody Hice (R) is the Georgia secretary of state. Once again, the Republican candidate (Donald Trump or someone else) loses the state by 12,000 votes. They call Hice and tell him to "find" enough votes to ensure a GOP victory. Hice says "Will do!"

How does he go about it? I doubt he cracks open the crate marked "Emergency Fake GOP Ballots."V & Z answer: It is entirely possible that Hice hasn't thought that far ahead, and that he's just saying what he needs to say in order to get Donald Trump's endorsement. So, Hice's promise might be nothing more than hot air.

That said, there was a time when creating a few votes (or a few thousand votes) out of thin air was plausible. In the past, we have related the (alleged) story of two Democratic operatives who headed to the cemetery to collect the names of enough "Democratic" voters to swing a close election. One of the two fellows spent an inordinate amount of time staring at a weathered tombstone, and the other fellow told him to move on if he couldn't parse the name. The first fellow refused on principle, declaring "This person has as much right to vote as anyone here!"

While the story is surely apocryphal, the practice of having dead people cast votes was most certainly real. But it would be nearly impossible to pull off today, particularly to the tune of 12,000 votes. In other words, Hice cannot plausibly deliver on his promise. What he might do, however, is find a way to disqualify the necessary number of Democratic votes. It would not be easy, but it's vastly more doable than creating 12,000 Republican votes out of thin air.

M.K. in Seattle, WA, asks: If I was going to do something illegal, why would I document any of it? How come the Trump folks have so many documents?

Even if one had some documents related to an illegal activity, why would one keep them around? Why would they not burn them or delete them? And how would the committee even know that these documents exist in the first place?V & Z answer: Well, the reason the documents exist in the first place is that you can't coordinate the activities of dozens of people (or more) verbally. Things need to be written down, in part to avoid miscommunication, and in part because human memory has significant limitations. Writing things down is no guarantee, as any teacher who has written a syllabus will tell you, but it's a far sight better than having no documentation at all.

On top of that, the people who participated in the events of 1/6 are now caught in an uncanny valley of sorts. As with, for example, the Nixon administration and Watergate, the Trump insurrectionists are all True Believers. They thought that what they were doing was righteous, or else they thought that what they were doing would be successful at keeping the president in power (and thus able to pardon federal lawbreakers), or they thought both of those things. Now, they are stuck between those two extremes. It turns out that they were not doing something just and righteous, at least not in the eyes of the people currently running the Department of Justice. It also turns out that they failed to sustain Trump in power. So, a year later, they are pretty exposed. But when they were creating these e-mails and memoranda and planning documents in the first place, many of them did not foresee things getting to this point.

So now that it is clear the conspirators could be in trouble, why haven't they destroyed everything? We can think of two reasons. The first is that some of the people involved, including Donald Trump, are legally required to document their activities. If there was a gap covering, say, three days in January, that would not only be suspicious, it would itself be overwhelming evidence of a crime over and above fomenting insurrection. This is true of other White House staffers, like Chief of Staff Mark Meadows.

Further, there is also, for lack of a better term, the prisoner's dilemma. Someone like Bernard Kerik or John Eastman might prefer to keep their documents to themselves. But if push comes to shove, they might need those documents to prove their "innocence" (or, at least, their lesser guilt) at the expense of their accomplices. Also, if Kerik destroys a memo on which he was included, and someone else who has that memo surrenders it to the 1/6 Committee or the Department of Justice, then Kerik would be caught red-handed destroying evidence. And the fact that hundreds of people have already cooperated with the Committee means that they already have a bunch of stuff, and they are aware of the existence of even more. Kerik has a very poor idea of what they do and don't have, so he's far better off coming up with excuses rather than destroying things.

D.E. in Lancaster, PA, asks: During the Cold War, scientists had a Doomsday Clock that they would set to show how close the world was to nuclear annihilation. Using that same metaphor, what time is it in regards to Donald Trump being indicted? In your opinion, did that clock move closer to midnight this past week or is that just wishful thinking on my behalf?

V & Z answer: Note that the Doomsday Clock still exists (it's currently 100 seconds to midnight).

It's a little tough to apply the concept to Donald Trump, however, because the whole point of the Doomsday Clock is that the world is dangerously close to nuclear annihilation. It's never been more than 17 minutes from midnight (that was right after the fall of the U.S.S.R.).

Just to give a foundation for our answer, let us imagine that Trump has spent most of his adult life at 11:00 p.m. on the clock. Dangerously close to indictment, and certainly closer than most people, but not in imminent danger. We would suggest he moved to 11:30 during his presidential campaign, 11:40 during his presidency (particularly with potential obstruction of the Mueller investigation), and 11:50 on 1/6. Note that some of these moves are driven not just by his actions, but by the higher profile and the higher desire to see him popped for something that came out of those actions. For example, Trump's behavior on 1/6 might get him indicted and it might not. But it's certainly going to give extra motivation to everyone who might possibly indict him (such as New York AG Letitia James).

The clock probably moved to 11:51 or 11:52 this week, primarily because the new Manhattan DA, Alvin Bragg, was clearly elected on the promise that he would make Trump pay. We assume that, at 48 years of age, he will do everything possible to deliver on that promise, with an eye toward moving on to bigger and better things.

So, let's say that Trump is currently at 11:51:30. He's in plenty of danger of being indicted, and is closer to that outcome than at any point in his life (even as someone who has spent decades flouting the law), but it's not quite imminent yet.

Politics

P.S. in Riverside, CA, asks: The Dow Jones average, a popular indicator of the U.S. stock market, hit its all-time high last month, and the market as a whole has performed incredibly well during the past year. While we all know that high stock prices are not the same thing as the economy, and don't really signify much to the common folk, they do mean a lot to corporate CEOs. I understand that Joe Biden doesn't set stock prices, so he is not directly responsible, but it is inarguable that he has set a national tone to which the market currently responds. Why then are so many business leaders, CEOs, Chambers of Commerce, etc. supportive of Republican administrations, while their portfolios overperform under Democrats?

V & Z answer: You should understand, first of all, that any tycoon, corporation, or lobbyist worth their salt plays both sides of the aisle. Democrats get plenty of corporate dollars, even if Republicans get more.

So why do the Republicans get more (at least, at the moment)? Well, the CEOs know they can't really buy a strong economy or a strong stock market. What they can buy (or at least encourage) is concessions/regulations favorable to their particular business or industry. And, at least in recent years, Republicans have been more amenable to those sorts of arrangements than Democrats have. In particular, Republicans have been much more willing to take money in exchange for rollbacks of environmental regulations.

It is also the case that the majority of CEOs are Republicans, and so are using the corporation's money to support their own personal political predilections. For example, Chick-fil-A gives a lot of money to Republicans because the Cathy family (which runs the chain) is socially conservative and, in particular, anti-LGBTQ+.

J.B. in Radnor, PA, asks: If the Republicans take back the House this November, I imagine most expect the House's 1/6 Committee will be shut down and its findings buried ASAP after the new House is sworn in. But couldn't Republicans in Congress go a step further and insert a poison pill into a must-pass bill requiring the Department of Justice to cease all investigations and prosecutions pertaining to the 1/6 insurrection? Would this be constitutionally permissible and if so how likely is it that Republicans would try this?

V & Z answer: It would be pretty hard to design something that would be less constitutional than this. The Department of Justice is part of the executive branch and is also supposed to be semi-independent of all three branches of government. Consequently, Congress has no right whatsoever to tell the DoJ what to do, and if they tried it would be a gross violation of the separation of powers.

Given that no court in the land would sign off on this, and given that it would raise uncomfortable questions (for instance, "What are you so worried that the DoJ might find?"), we cannot imagine the Republicans would try this.

M.C. in Auburn, WA, asks: Can you give me any hope that the Republicans will not gain control of Congress this November? Any hope at all?

V & Z answer: Certainly. Here are eight things to keep in mind:

- As we have pointed out many times, something like 90% of districts are "safe" for one party or the other. When it's a small number of seats—maybe 30 or 40 of them—that will determine control of the House, then unexpected outcomes are more probable. That is to say, the Democrats don't need dozens of lucky breaks, they only need a handful.

- The Republicans did very well in House elections in 2020, and also in the round of redistricting/gerrymandering that happened after the 2010 census. They are already somewhat close to their peak in terms of how many seats they can plausibly hold.

- We're still 11 months from the election and Republicans are getting overconfident, while also indulging in intra-party squabbling (as we pointed several times this week). We saw how well those behaviors worked out for the Democrats in the supposed "blue wave" year of 2020.

- There are three midterm elections in the last century where the party in the White House did not lose seats: 1934, 1998, and 2002. Each of those was likely caused by a rather prominent issue that affected the mindset of the electorate—to wit, the New Deal, the looming Clinton impeachment, and the 9/11 attacks. If Roe v. Wade is overturned, that could very well be one of those sorts of issues.

- Similarly, the notion that Donald Trump and Trumpism are fascist/fascist-adjacent, and represent a special threat to democracy, is really starting to take hold. That could motivate otherwise low-engagement Democrats to get out to the polls for the midterms.

- And speaking of midterm engagement, there are a lot of important, and potentially close, Senate races on a map that generally favors the Democrats. Those races could also motivate otherwise low-engagement Democrats to get out to the polls.

- Meanwhile, the extent to which a realignment is underway, and what the effects of that realignment might be, are currently unanswered questions. There is a distinct possibility that a lot of the people who skip midterms (e.g., noncollege men) are now Republicans, and a lot of the people who always make sure to vote (e.g., educated suburbanites) are now Democrats.

- And finally, Donald Trump could serve not only to get Democratic voters to the polls, but also to keep Republicans away. It could be as simple as the Trumpers being less interested when he himself is not on the ticket. Or his "stop the steal"/"it's all rigged" rhetoric might make some portion of his base say "What's the point?" This will be particularly true if one of Trump's favored candidates loses in the primaries (e.g., Herschel Walker or David Perdue in Georgia) and he throws a temper tantrum (as he did in advance of the Georgia special elections that elected Sens. Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, both D-GA).

Republican control of the House is still the likeliest outcome. But for all of these reasons, it most certainly is not a slam dunk.

M.M. in San Diego, CA, asks: I love the Aussies' "democracy sausage" tradition! With a little tweaking, it could make an excellent Election Day lure for the 18-29 demographic here. What should we use for bait? Avocado toast, or is that over? A "best vegan fare" competition among local restaurateurs? Maybe just have José Andrés or Joe Yonan create a set menu that the DNC can duplicate at polling places in every college town? (Z) has vast knowledge of American youth. What say you?

V & Z answer: When your question initially hit the inbox, and then when (Z) went back to answer it, the same answer occurred both times: Boba tea. It's popular, cost-effective, portable, and a special treat for most people. It can also be customized to accommodate various dietary needs (sugar free, vegan, etc.)

If readers have other ideas, send them in, and we'll run some tomorrow.

M.B. in Cleveland, OH, asks: You wrote about the 2021 election in the Netherlands, and linked to the Wikipedia page about them, which includes this passage: "The election had originally been scheduled to take place on 17 March; however, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the government decided to open some polling stations two days in advance to ensure safe voting for elderly and immunocompromised citizens. Citizens aged 70 years or older were also given the opportunity to vote by post..."

Two days of early voting, one time only, and only at some polling stations? Vote by post only for those 70 or older? This is much more restrictive than the voting rules that people denounce in Texas, Georgia, and other states. Not to give the Republican Party too much credit, but if restrictions like this are fine in a solid democracy like the Netherlands, why are they so onerous in the United States?V & Z answer: Traditionally, there was no early voting and no absentee voting in the Netherlands. Voting on Election Day was the norm and worked fine. There were plenty of polling places and waiting to vote never took more than 10 minutes. Also, the entire election administration is run by nonpartisan civil servants. Traditionally turnout was north of 80%, in part because all residents are required by law to be registered with their municipal government, so there is a single database for voting, taxes, drivers' licenses, "Social Security," etc. The new measures were introduced in the Netherlands on account of COVID. For people physically unable to get to the polling place, they could give a "power of attorney" form to a family member to vote for them.

The U.S. only began to experiment with early voting in the 1990s, and it wasn't until the 2000s that the percentage of votes cast early reached double digits (16% in 2000, 22% in 2004, etc.). Absentee voting has been available since the Civil War but was rarely used until fairly recently.

If all the Republicans did was reduce early voting, that would not be so bad, but they also did things like:

- Reducing the number of polling places to make the lines hours long

- Requiring ID that some people don't have and that is hard to obtain

- Having armed partisan poll watchers allowed at polling places

- Having one polling place in a county, or one absentee ballot box, and putting it far from public transit

The net effect of these laws was to make voting more difficult for poor people, people of color, women, college students, and other groups that skew Democratic. And so, they were discriminatory, and were crafted to serve a clear partisan purpose. By contrast, the Dutch laws were crafted in response to a public health crisis, and were not designed to help a particular party or parties.

Civics

F.S. in Cologne, Germany, asks: Is the U.S. Constitution a living document?

V & Z answer: This notion was first put forward in the 1927 book The Living Constitution, by legal scholar Howard Lee McBain. The argument basically boils down to two main assertions: (1) the Constitution is adaptable to new and different circumstances, as they arise; and (2) the document was purposefully left open-ended and general, so as to make sure that was the case.

The first part of that seems like common sense to us. Clearly, the Constitution has been adapted to new and different circumstances, since the original document makes no mention of, say, abortion, or immigration, or a military draft. At the same time, there are elements of the document—like the three-fifths compromise—that have been put aside. Now, we are not legal theorists, and so it's possible that someone who is more expert than we are could make a compelling case that these things aren't "adaptations," and are clearly rooted in the original text of the document. It's not likely, we think, but it is at least possible.

On the other hand, one of us is a historian, and so can definitely speak as an expert to the second point. And there is simply no question that the fellows who wrote the Constitution, and who came from the highly adaptable English common law tradition, absolutely meant for it to be a framework that grew and changed with the times.

E.W. in Skaneateles, NY, asks: You wrote: "in theory, [SCOTUS has] an indeterminate amount of time to decide" on the Former Guy's appeal about executive privilege. What kind of deadlines, either de jure or de facto, does SCOTUS actually have? What would happen if they missed them? Has any SCOTUS ever intentionally "run out the clock" on an important case?

V & Z answer: The Supreme Court's own website says this:

There is no law or rule requiring the Court to act by a time certain, but as a practical matter, an application by definition implies a deadline of some sort.The first part is clear and helpful but the second part... less so. After all, the fact that the sun will burn out in 4 billion years or so also "implies a deadline of some sort."

And the Court does not, as a rule, "run out the clock" in the way you suggest. We're not saying it's never happened, especially since there are generally only nine people who know for sure, but if they want to avoid a touchy ruling, they just decline the case. If the Supremes take it, it would be too obvious if they sat on it for months (or more) just as a favor to a politician or political party.

There is a different form of delaying tactic, though. On occasion, when a justice no longer seemed competent (for example, William O. Douglas at the end of his career), the other members have reached agreement not to let that justice be the deciding vote on any case, and to hold off until they retire.

C.S. in Madison, WI, asks: Why are parliaments designed so that a ruling coalition needs to be created? Why not just start voting on laws (and prime ministers, etc.) without any formal binding of individuals and parties into a coalition?

V & Z answer: You have essentially answered your own question. Generally speaking, one of the first things that a newly elected parliament has to do is choose one of their own to become prime minister. And that decision generally requires a majority of members to vote in favor of that person (either directly or, in some cases, indirectly).

In other words, what "ruling coalition" really means is "a majority that is willing to unify behind a particular candidate for prime minister." So, once a prime minister is chosen it means, de facto, that a ruling coalition exists. And parliamentary systems tend to be set up such that it behooves that ruling coalition to remain intact once its members have backed a prime minister. For example, if a minor party gives five votes to put a candidate over the top, they usually get some legislative concession in response, like "The new government agrees to support a bill that will extend maternity leave by two weeks." That minor party better remain on board with the coalition if they want their reward, and if they want to have an ongoing voice in governance.

History

A.B. in Delray Beach, FL, asks: Recognizing most readers are familiar with the concept of history being written by the winners, I am curious as to your thoughts on this. A year ago, most of the country watched in horror as the events of January 6 occurred. At that time, the vast majority of the country, regardless of party, denounced what transpired. Since that time, the big lie has been perpetuated repeatedly, to the point most Republicans concur the election was stolen and they have bought into (what appears to most thinking people to be) a complete alternative reality, unfettered by any pesky facts. They make the case the events of that infamous day were no big deal, and what we saw with our own eyes did not occur.

Since this is the case, how do you believe history would have recorded the events of the day, had the coup been successful?V & Z answer: While we recognize that "history is written by the winners" is a well-worn aphorism, and might seem to make sense, it's not an especially truthful aphorism. It's not uncommon, in fact, for history to be written by the losers, since the losers often have a need to justify themselves and to make themselves feel better about having lost. The post-Civil War South is the famous example of this, but the same thing has happened in many other places. If anyone would like to read a detailed analysis, the classic work is Wolfgang Schivelbusch's The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery, which examines the rather significant parallels between the post-Civil War South, post Franco-Prussian War France, and post-World War I Germany, and the stories that those folks told themselves and others.

In the vast majority of cases, however, history is neither written by the winners nor the losers, it's written by... both. With relatively rare exceptions, there are competing narratives about nearly all historical events and personages. Think of Christopher Columbus (great explorer vs. committer of genocide), Father Junípero Serra (preeminent man of God vs. evil colonialist), Thomas Jefferson (towering leader and philosopher vs. hypocrite and rapist), 1619 (still shaping our society vs. so long ago it's not worth discussing) or the New Deal (saved the country vs. creeping socialism). We mention these examples because both sides of the narrative are pretty well known, but you can be sure there are competing narratives—often many of them—for any major historical personage, event, or era.

And so, even if 1/6 had turned out differently, historians would be well aware of both sides of the incident and would certainly teach both sides. After all, it's not really possible to understand an event without that. Consider the American Revolution: There's been more than two centuries for the dust to settle, and there's a broad consensus that the rebels were in the right. Still, any lecture on that era is going to explain where King George III and Parliament were coming from, and is probably also going to mention the viewpoint of American loyalists. Without the former, you can't really understand the tit-for-tat that took place between the British government and the American rebels, and without the latter you can't really understand why it was so difficult to recruit and sustain a rebel army.

Finally, note that presenting/discussing multiple perspectives, including how they changed over time, is not the same thing as endorsing those perspectives. (Z) has given hundreds of lectures and talks on the "Lost Cause"—what it was, why it emerged, how it changed over time—but that certainly doesn't indicate that he's a neo-Confederate.

H.F. in Pittsburgh, PA, asks: In response to the 2021 predictions of S.B. in New Castle, (Z) wrote: "... [Trump is] like the Civil War. No matter how you make the movie, you're either going to piss off the red states or the blue states." That got me wondering, what would (Z) say were the best and worst Civil War movies? For what it's worth, I thought Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter wasn't as ridiculous as its title sounded. Comparing slave owners to vampires sounds about right to this Yankee!

V & Z answer: The great film critic Roger Ebert explained many times that he attempted to judge a film based on what it set out to do, and not in comparison to all films that have ever been made. What that means is that a movie like, say, Avengers: Infinity War cannot compare to Casablanca or The Godfather, but as a comic book movie it's four stars and thumbs up (he used stars in print and thumbs on TV). Unless a person completely missed the title, then when they sat down to view Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, they surely knew it was tongue-in-cheek and that to the extent that it had something to say about the Civil War, it was going to say that through metaphor. And if you understand what it was trying to do, well, it was reasonably successful at doing it. Ebert, for his part, gave it three stars, and described it as "the best film we are ever likely to see on the subject." That said, while the film is OK-to-good, there are a lot of Civil War films, so it doesn't crack the Top 10.

Before we get to the lists, a couple of notes. First, we're not going to include documentaries or miniseries. Second, there is not always a bright-red line between "Civil War film" and "not a Civil War film." To make the cut here, a film has to take place during the war, or significantly engage with the causes of the war, or significantly engage with the consequences of the war, or be built around key people from the war. Also, we think we have successfully avoided spoilers by speaking only in a very general sense of the plots of the films.

Before we get to the two lists you asked for, we're going to mention two films that we're not going to rank at all:

- Gone with the Wind (1939): It's epic. It's influential. It features great acting. Adjusted for inflation, it's still the highest-grossing film of all time. On the other hand, it's terribly racist, it's a Confederate apologia, and it's done in a style that doesn't connect with many modern moviegoers. It could plausibly be on the "best" list, or the "worst" list, or both. Hence the non-ranking.

- The Birth of a Nation (1915): This one is even more epic and more influential than Gone with the Wind (though the acting, while period- and silent-film appropriate, is pretty bad). It may also be one of the top-grossing films of all time, adjusted for inflation, though we'll never know for sure because bookkeeping back then was pretty spotty. However, the film has even greater watchability issues than GWTW does. Whereas the racism of GWTW is passive (or passive-aggressive), the racism of The Birth of a Nation is unfiltered and over the top. Black stereotypes? Check. Blackface? Check. Making heroes out of the KKK? Check. On top of that, beyond the hammy acting, it's also silent and is in black and white (or, in some presentations, sepiatone). That really doesn't work for many modern moviegoers (though another silent film did make our list). Anyhow, this is another one that could be on either list, and that we will therefore leave unranked.

And now, the 10 best Civil War films (well, technically, the 11 best), in reverse order:

- (Tie) Gettysburg (1993) and Little Women (2019): We put these two together because they are yin and yang. Gettysburg focuses almost exclusively on male characters and the war front. Little Women focuses almost exclusively on female characters and the homefront. They are both pretty well done, but the Venn diagram of "fans of Gettysburg" and "fans of Little Women" must surely be two circles that barely overlap. So, if you find one of them to your liking, you probably won't be a big fan of the other.

- The Red Badge of Courage (1951): An excellent adaptation of the finest novel written about the Civil War, and starring the great Audie Murphy.

- Cold Mountain (2003): A solid script, good directing, and great acting in a film that—within the constraints of the Hollywood storytelling—does a fine job of complicating the story of the Confederate homefront.

- Shenandoah (1965): When you start by casting Jimmy Stewart, you already have a leg up. And this is a compelling tale of a family that tries desperately, albeit unsuccessfully, to avoid being dragged into the Civil War. It's also great for teaching purposes, if one wants to show how historical films are often shaped by contemporary concerns. When Charlie Anderson (the Jimmy Stewart character) says things like "There's not much I can tell you about this war. It's like all wars, I guess. The undertakers are winning. And the politicians who talk about the glory of it. And the old men who talk about the need of it. And the soldiers, well, they just wanna go home," in a film released in 1965, it's rather obvious that he might just be describing some other war in addition to the Civil War.

- The General (1926): You wouldn't think the Civil War could be turned into a comedy. That said, you wouldn't think that would work for the Nazis, either, and yet look at The Producers, Hogan's Heroes, and JoJo Rabbit. Anyhow, Buster Keaton's silent masterpiece about a stolen Confederate train was enormously influential, particularly in terms of early stunt work, and it still holds up.

- 12 Years a Slave (2013): This takes place before the Civil War, but it certainly meets our requirement of significantly engaging with the causes of the war. Like Steven Spielberg's Amistad, 12 Years a Slave is based on a true story about illegally captured slaves. However, 12 Years a Slave is a considerably better film, and does a much better job of conveying the horrors of the institution.

- Django Unchained (2012): This takes place right before the Civil War (on screen, the film says 2 years, but it's really 3 years), and it's also about the horrors of slavery. In contrast to 12 Years a Slave, the characters and events are fictional. In fact, everything is grossly exaggerated, consistent with director/screenwriter Quentin Tarantino's style. The movie is meant to be part of a "revenge trilogy," along with Inglourious Basterds and an as-yet-unknown third film, in which historically oppressed peoples gain (ahistorical, fictional) revenge against their oppressors. It's also gripping—the first 20 minutes alone are worth the price of admission, even if the film does drag a little at the end. (Z) actually saw it at the theater that belongs to Tarantino (the New Beverly Cinema).

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966): You know the argument about how Die Hard is or isn't a Christmas movie? Well, some folks debate whether this is or is not a Civil War movie. However, while you can argue it either way for Die Hard, there is no argument for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. The Clint Eastwood "spaghetti western" is set during the Civil War, the treasure the main characters seek is Confederate gold, and the movie is clearly based on the Civil War's New Mexico campaign. It's one of the greatest Westerns, and one of the greatest Civil War films, ever made; the climactic standoff at the end is legendary.

- Lincoln (2012): This is a magnificent movie, featuring a brilliant performance from Daniel Day-Lewis and a first-rate supporting cast. It's also a rare example of Steven Spielberg engaging in some restraint while making a historical drama. The movie is not everyone's cup of tea, since the tension is rooted in shrewd and often subtle political maneuvering by the 16th president. But if you're not interested in political maneuvering, then why are you reading this site?

- Glory (1989): It plays a bit fast and loose with the historical facts, in particular whitewashing Robert Gould Shaw's racism. Nonetheless, the story of the first formally organized all-Black combat unit, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, manages to squeeze a fair bit of historical truth into a powerful bit of cinema. It remains the gold standard for Civil War films.

And now, the five worst Civil War films:

- CSA: The Confederate States of America (2004): Based on letters to the Sunday mailbag, we know some readers appreciated this faux documentary that imagines a world in which the Confederacy won the Civil War. Other than the faux commercials, however, (Z) wasn't a fan. The film begins with the ahistorical notion that the South was looking to conquer the North (they were not; the Confederacy just wanted to be allowed to go their own way). And from there, it beats you over the head with its MESSAGE. It's also one-note; if you see 10 minutes of the film, you've basically seen the whole thing.

- Gangs of New York (2002): Even the talent of Daniel Day-Lewis (and Leonardo DiCaprio) couldn't save this, one of Martin Scorsese's weakest films. It does a great job of creating the look and feel of Civil War-era New York, but the plot is meandering and uninteresting. Exiting the film, (Z) said to his companions: "It seems like they were writing the screenplay while they were making the film, with no idea where it was heading." It turns out this is basically correct.

- Wild Wild West (1999): This is set after the Civil War, but one of the heroes is a Union veteran, the main villain is a Confederate veteran, and Ulysses S. Grant is the president. So, it's a Civil War film, in our view. And it's understandable how a pitch of "steampunk Western!" "starring Will Smith!" "and also Kenneth Branagh and Kevin Kline!" got greenlighted. But the film just does not work. Sometimes, a huge budget, great special effects, and heavy-duty acting talent can't overcome a lousy screenplay.

- Free State of Jones (2016): Filmmakers love to take quirky, little-known stories and to make movies out of them. That's what's going on here, a movie based on a real person, a Southerner who resisted the Civil War from behind the lines. However, it doesn't click, and Matthew McConaughey demonstrates that while he can nail roles that are just right for him, his range is limited. Plus, through the implication that there was significant Southern resistance to the war (there wasn't), the movie comes dangerously close to Lost Cause thinking.

- Gods and Generals (2003): This is a prequel to Gettysburg, and it's nearly 4 hours long. (Z) has only ever walked out of one film in his life (Natural Born Killers), but this would have been the second if not for professional obligations to see it through. There is no plot to speak of, first of all, and therefore no need for the oversized runtime. Further, Gettysburg was based on a book by Michael Shaara, who had a talent for writing dialog that sounded like 19th century speech. Gods and Generals is based on a book by Shaara's son Jeffrey, who doesn't have that skill, and compensates by using the characters' actual words. The problem is that those words were written, and it doesn't work to turn written words into spoken dialog (especially with the denizens of 19th century). Worst of all, while The Free State of Jones is Lost Cause-adjacent, Gods and Generals is full-blown Lost Cause. For example, Confederate general Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson is portrayed as something close to an abolitionist. That's problematic for a film made in 1939. It's inexcusable for a film made in 2003.

There you have it—(Z)'s Civil War filmography.

T.B. in Bozeman, MT, asks: The Atlantic Monthly has just published a precis of Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition, a new book by Mark Lawrence Schrad, a political science professor at Villanova. His position seems to be a thorough-going revision of the subject, at least from an American perspective. He claims Prohibition was a progressive initiative, with the pious crowd merely yap-dogs yipping impotently in the wake. Perhaps my various American History professors just liked to liven things up with piquant tales of hatchet-wielding, Bible-toting Carrie Nation, but were she and her ilk not all that critical to the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment? I wonder what you professional experts make of his thesis?

V & Z answer: We'll start by pointing out two things that are true of the historical profession. The first is that each new generation of historians develops and explores new approaches, perspectives, etc. that were not used (or not widely used) by past generations. Looking at issues transnationally or globally has been hot stuff for 20 years or so (in other words, since right around the time Schrad was beginning his career), but was not especially common among Americanists before that.

Second, every historian benefits from framing their interpretation as groundbreaking, revolutionary, etc., and completely overturning everything previously thought about subject [X]. They usually believe it, and sometimes they are even right, but usually it's a bit of an over-sell. Or a huge over-sell.

(Note that these dynamics undoubtedly exist, in general form, in every academic discipline. However, we're zooming in on U.S. history here because it's a U.S. historian.)

Anyhow, it is certainly the case that Schrad highlights some things that are generally not covered in American history courses' Prohibition lectures. Certainly, most students are not aware that Prohibition was a global phenomenon, and had analogues in many nations beyond the United States. Similarly, most students are not aware of the contributions of some groups to the movement, including minority groups and Progressive leaders.

That said, to make his globally oriented argument, Schrad massages the evidence an awful lot. Even from the piece in The Atlantic, it's clear that, say, the Prohibition movement in the U.K. and its colonies (e.g., India) was not really all that similar to the American version. Further, Prohibition in the United States was ultimately imposed through a constitutional amendment. That can't happen unless there is broad support from many different interest groups. Any Ph.D. in U.S. history knows that it wasn't just religious folks ("alcohol use is immoral!"), it was also Progressives ("alcohol use promotes crime," "Big Alcohol has too much power!"), leaders of minority groups ("alcohol is a tool used to keep our communities under control"), xenophobes ("it's the foreigners, particularly the Catholics, who are the drinkers"), women's rights activists ("drunk husbands often turn abusive") and a bunch of others.

If the lecture you heard emphasized Carrie Nation and the religious activists—who most certainly were an important part of the movement, if for no other reason than all the publicity they generated—then that may be because your professors were reflecting the scholarly understanding that was prevalent when they were educated. However, it is also the case that: (1) Prohibition is not that important (it only lasted a decade, after all), (2) time is very limited in a survey course, and (3) exploring the full complexity of an issue/event/era is very difficult and very time-consuming. Someone like Carrie Nation is easy to explain, easy to remember, and her story captures much of the "juice" of Prohibition, even if the full story is much more complicated.

M.M. in Plano, TX, asks: Last year, we exchanged words on the anachronisms in the PBS series Atlantic Crossing. I left out the whopper of all whoppers. The series shows Franklin D. Roosevelt meeting with a group of isolationist Congressmen about a year before Pearl Harbor. Among them are at least two Black men. In the Congress, in 1941.

V & Z answer: You did not submit this as a question, but we're going to treat it as one, so we can respond fully. As with the other things you asked about last year, this is not 100% accurate, but it's not 100% wrong, either.

The member of Congress who is clearly being referenced is Arthur Wergs Mitchell, who represented the same district as Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL; more on him below). Mitchell was the first Black person to be elected to Congress as a Democrat, and who was the only Black person in Congress during his entire term in office (1935-43). And he actually was an isolationist, since he felt the U.S. had more pressing issues to worry about at home, like lynching.

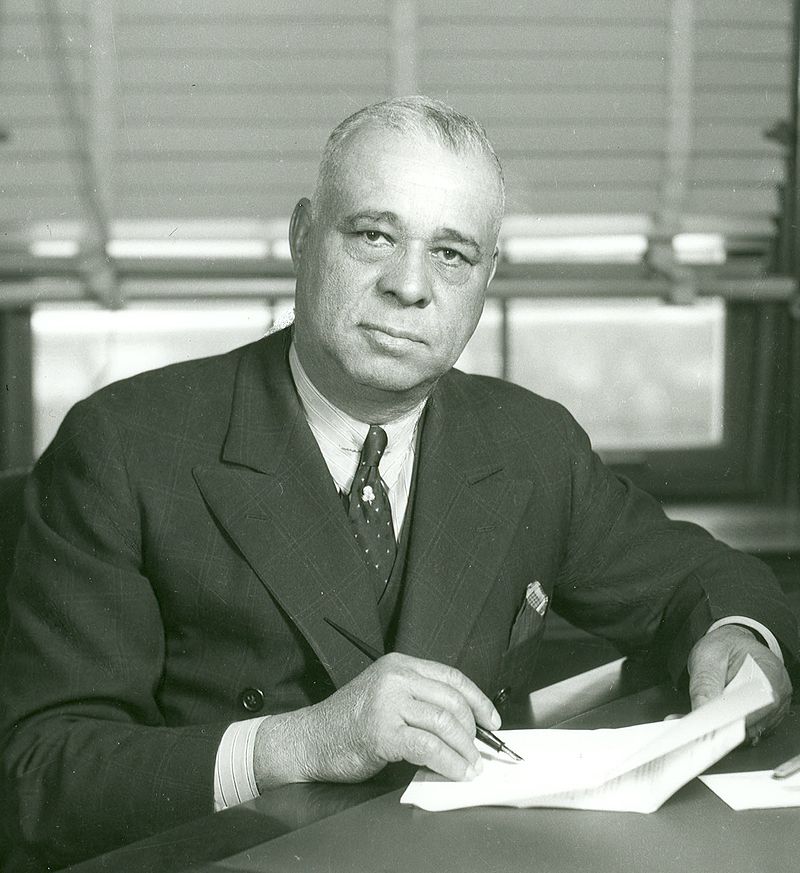

Again, we have not seen the series. If it is implied there was more than one Black member of Congress, then that is not true. Similarly, to emphasize "diversity," we suspect the actor who played the role was noticeably and unquestionably Black. However, the real Mitchell was more ambiguous:

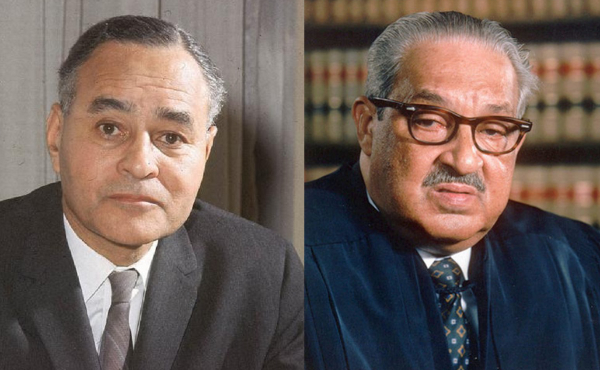

Given the racism of the day, both overt and latent, that sort of ambiguity was essential, or nearly so, for any Black person who wished to have a high-profile career in public service. Consider, for example, Nobel laureate and diplomat Ralph Bunche, or judge and solicitor general Thurgood Marshall:

Their heritage was not a secret, per se, but their appearance was enough to keep them from triggering a visceral, pre-programmed racist response from many white folks.

Gallimaufry

C.P. in Silver Spring, MD, asks: I recently saw this comment on Twitter describing UCLA as far superior to Harvard. Can (Z) offer his opinion on this, just out of curiosity?

V & Z answer: To start, (Z) has told his students many times that a person can get a good education at any university or a bad education at any university. It's largely on the student to determine which one they get.

Anyhow, the central thrust of the tweet is that UCLA has better students than Harvard, on average, because Harvard admits so many legacy students, and they drag the overall standards down. (Z) would not want to say that one group of students or another is better, since that is a hard thing to judge, and since he doesn't have that much knowledge about the Harvard student body. However, (Z) would certainly agree with the point that is made in a follow-up tweet, namely that the UCLA student body has a more diverse range of backgrounds and experiences.

Beyond that, if a person was trying to choose between Harvard and UCLA, and asked (Z) for advice, he would say three things. The first is that the Harvard name opens a lot of doors for graduates. The UCLA name does, too, but not as many as having a Harvard diploma does. There are some fields where that doesn't matter too much, but there are also some where it matters a whole lot.

Second, there's a lot of pressure on UCLA students, but it's nothing like the pressure that is exerted upon Harvard students. There may be grade inflation in Cambridge and so, depending on one's major, coursework may or may not be a source of much stress. But one's peers certainly are, as Harvard tends to have a lot of people who view themselves as overachievers, either due to their own accomplishments or those of their family. Some people who enroll at Harvard really struggle to deal with the cutthroat competition.

Third, at UCLA, the professors actually teach. At Harvard and other Ivies, they get tons of release time, and many of the really prominent folks never teach at all. So, if you're an undergrad at Harvard, you are going to get a lot of courses from visiting instructors or, increasingly, postdocs. Your chances of getting a class with Amartya Sen or Steven Pinker or Claudia Goldin are not great. On the other hand, you can absolutely get a class with Michael Dukakis or Judea Pearl or Terence Tao at UCLA.

M.M. on Bainbridge Island, WA, asks: This week, you wrote: "We actually have a bunch of other content pending, but there are only so many hours in a day."

I have long been curious about how much time you put into your site. How many hours do you spend researching and writing each day's content, following polls, etc.? I know you each write on alternate days, but do you work together behind the scenes on those days? I was only introduced to your site a little more than a year ago, and I read it every morning, but I've been amazed that in that time you have never missed a day, even for holidays. (And I have to say I'm one of those who is not happy that you've shortened each day's post, although I know others are.) Basically, I'd like to know what's involved in maintaining your site.V & Z answer: First, note that we only shortened the Sunday mailbag.

Anyhow, most days it takes between 3 and 6 hours to produce that day's post. We also keep an eye on various news sites throughout the day and week, but that's a few minutes here and a few minutes there, and would be hard to add up in any sort of accurate way. We do consult on some items, and on top of that, multiple times per week, one of us writes an item and the other adds to it or otherwise significantly modifies it.

There are also some items that take extra time (often a lot of extra time) to produce. As a general rule, as length increases, time and difficulty increase geometrically rather than arithmetically. That is to say, a 2,000-word item is not twice as hard to write as a 1,000-word item, it's more like four times as hard. It's also tougher if an unusually high number of sources (like, dozens) are consulted, as was the case for this week's item on foreign elections, to take one example. Anything that has to be compiled, like reader predictions, tends to take extra time. And some items present special challenges of a technical sort. Hopefully, one of those is coming up this week, if we can work out the kinks.

S.G. in Durham, NC, asks: You wrote: "Rep. Bobby Hill (D-IL) announced that he was stepping down on Monday..."

This one? Or this one?V & Z answer: We got quite a few e-mails about that error, which we did go back and fix, of course. Due to some unfortunate luck with scheduling, (Z) wrote that while also dealing with the effects of the COVID booster shot. Anyhow, nearly everyone suggested it was a King of the Hill mixup, but it actually wasn't. It was a mixup with (Z)'s now-retired colleague at UCLA, who is also named Bobby Hill.

B.K. in Dallas, TX, asks: I would like to post some of your stuff on Facebook. Would you have a problem with that?

V & Z answer: We are always happy to have our material be shared, whatever the platform might be. Right now, if you post a link to Facebook, it just provides a generic preview, as opposed to a preview of that specific item. We hope to correct for that eventually.

Previous | Next

Back to the main page