The voters hate gerrymandering. Numerous polls have shown that. For example, this one from Noble Predictive Insights shows that 84% of registered voters think how the district maps are drawn is important for the health of democracy and 77% want independent commissions to draw the maps.

Or, to approach the question in a different way, consider this comment sent in after the election by reader J.H. in Boston, MA:

You write how big a victory the Proposition 50 win is for Gov. Gavin Newsom, which it surely is. It is also a big win for the big-D Democratic Party, whose position seems as weak as it's ever been in my lifetime right now. And it was necessary to stop the complete takeover by MAGA. You can't fight a war where one side unilaterally disarms and the other doesn't. So don't get me wrong, I'm glad it passed.

But I don't agree with all the jubilation and celebration I'm seeing online about this win. And I don't agree with people calling Arnold Schwarzenegger a POS for opposing it. It's a loss for small-d democratic government, and a loss for good governance. It's opening the floodgates for other states to respond in kind, it's an escalation in the gerrymandering arms race, and it won't stop here. Proponents made a lot of noise about how it's only temporary, but like, that's only if Texas and the rest somehow reverses their gerrymanders, which I don't see happening. I expect doubling down. Then California is going to need another constitutional amendment just to keep the status quo, and there will be enormous national pressure to ensure they do.

We shouldn't be celebrating this victory, we should be mourning it, while still acknowledging its necessity. This is going to end with a much less democratic system. And you can't really claim to be the "pro defense of democracy" party while doing antidemocratic moves justified by "well, the other party is worse." Where does it end? Maybe congressional delegations become winner-take-all, like the Electoral College already is (in all but two states).

We think J.H. is right in several ways, to wit: (1) gerrymandering is very anti-democratic, but (2) most voters see it as less bad than the current alternatives (i.e. to let MAGA trample all over the Constitution), and (3) that we're watching the start of an arms race. If you think gerrymandering is everywhere now, just wait until the Supreme Court guts what's left of the Voting Rights Act in a few weeks, and then every state in the South tries to carve up all the minority-majority districts in their state. That is not guaranteed to work, because if a state is 70% white Republican and 30% Black Democrat, and 30% of the whites want to send a message about gerrymandering, Democratic candidates could actually win some of the new districts. Still, arms races are not always rational.

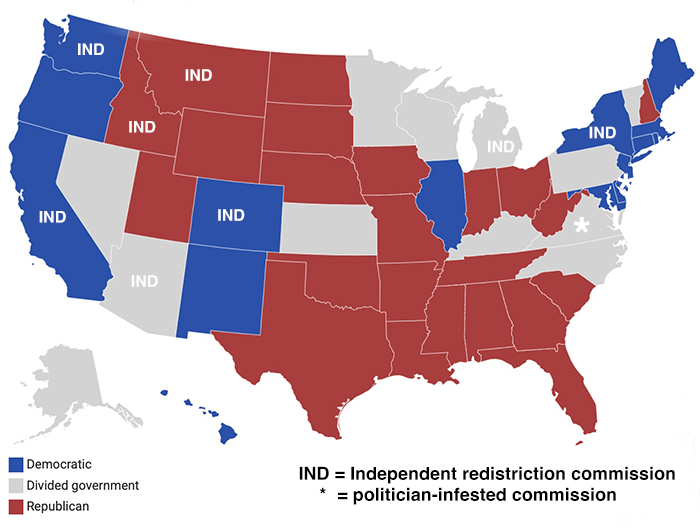

At the very least, the ensuing gerrymanderfest will get a lot of attention. If the Democrats win the House in 2026, they could pass a bill banning gerrymandering in one way or another, but it probably won't get though the Senate and if it does, Donald Trump will veto it. This is due to simple math. Here is a map showing which states have trifectas:

There are 23 Republican trifectas and 15 Democratic trifectas, so the Republicans have more opportunity to gerrymander the maps. But it is even worse than that. Of the nine states with truly independent redistricting commissions, four are (large) blue states (California, Washington, Colorado, and New York) plus Hawaii. Only two are red states, and low-population ones at that (Idaho and Montana). Arizona and Michigan have independent commissions but mixed state control. So not only do the Democrats have fewer states to gerrymander, but they have voluntarily given up that weapon in five of them. As a consequence, Republicans have little interest in getting rid of gerrymandering. Still, if a Democratic House passes a bill to end gerrymandering and a Republican Senate or Republican president kills it, that could be a potent issue in 2028. You never know.

If the House (or later both chambers) passes a bill requiring independent commissions, the devil is in the details. How can a law ensure that the commission is truly independent? For example, if the bill stated that the largest and second-largest parties in the state Senate and state House/Assembly each nominated one member of the commission and the governor nominated the fifth member, the commission would draw a wildly gerrymandered map favoring the governor's party. This would be worse than worthless, since it would have the aura of independence without any actual independence.

This is not to say that it can't be done, but the details matter. Suppose that the four legislative leaders each got to pick two members and that was it. An eight-member commission. To ensure a neutral map, throw in a rule requiring a three-quarters majority (six members) to get the map approved. What would happen if they couldn't agree? The law could state that until they agreed, there could be no House elections and no members seated. So the state would be punished for unwillingness to draw a fair map. Would that do the job? No. Suppose the California Republicans refused to compromise and California had no representation in the House. From the perspective of California voters, this is a bad deal, but from the perspective of the national Republican Party, this is a very good deal because even a fair map of California (as was the one drawn up in 2021) would result in a lot of Democrats being elected. Better no representatives than a bunch of Democrats.

Of course, Texas and Florida Democrats would also balk, so those states wouldn't have any representatives either. Rinse and repeat in every state. In the end, the House would have six members, from Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming, since those states have only one representative so there is no map and no need for a commission.

Is there a better way? In this super partisan era, only maybe. One way would be the above eight-member commission, but with a panel of judges hiring a special mapmaster in the case of a deadlock. Even then, though, most judges were appointed by a president or governor. Would the Texas Supreme Court, with seven Republican appointees, really pick a truly neutral special master? We're not so sure. So, how do the states that have independent commissions do it now? Let's take a look at a few of them.

If you are looking for an overview of redistricting, here is a good one.

Of the various schemes, California's is probably the most difficult to game since random draws are used in the process and the initial pool is very large. The worst schemes are those in which each legislative leader picks one member and they pick a fifth member, with voting fifth members the worst of all.

In all the schemes, the possibility exists that a commission member could be bribed into accepting a biased map. The best defense against that would be to require unanimous consent to accept a map, or at least a supermajority. This is especially effective if the commission is fairly large, such that multiple members would have to be approached with offers, with the danger that the approachee might rat on the person offering the bribe. (V)