Previous | Next

Senate Unveils Relief Package v3.0

With so many COVID-19 relief packages flying around, it's easy to get a little confused as to which is which. That's certainly what happened to us yesterday; aided by a little bit of clumsy wording in the New York Times story we linked to, we were left with the impression that the biggie (the $1 trillion package) was a done deal. Actually, it's relief package v2.0 (the $8 billion package) that got signed into law on Wednesday. The $1 trillion package is now on deck.

Should you have any doubts that the modern-day Republican Party, particularly when Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) is making the calls, has absolutely no interest in bipartisanship, this situation should put those doubts to rest. Back in the 1980s, when the staunchly liberal Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill and the staunchly conservative president Ronald Reagan needed to get something done, they would each make their speeches, and then they would get together and figure out a compromise that both sides could live with. This is also what happened with COVID-19 relief bill v2.0; with the Senate out of town for the week, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) & Co. got together with the Trump administration (represented by Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin), and came up with something both sides could live with. By contrast, the bill unveiled by McConnell on Thursday was crafted with zero input from Democrats. If the Majority Leader can't play nice with the other side under these circumstances, then he can't play nice ever. Asked about his total disregard for bipartisan cooperation, McConnell shrugged and said, "Trust me, this is the quickest way to get it done."

To be blunt, we do not trust him. And predictably, his proposal has already become a political football, with Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) describing it as a "non-starter." Here is what the McConnell plan envisions:

- "Recovery Rebates": Payments of $1,200 for (some) individuals or $2,400 for (some) married

couples, increased by an additional $500 per child. The rebates would be based on 2018 tax returns, and would be reduced

by $5 for every $100 above $75,000 earned by an individual, or above $120,000 for married couples. People with no tax

liability for 2018, and thus no tax return, would be eligible for up to $600.

- $300 billion in loan guarantees for small businesses: The loans would potentially be

forgivable, and business owners would be required to use them for salaries, mortgage payments, and payroll, including

paid sick, medical and family leave. That said, this provision of the McConnell bill would actually reduce employers'

responsibilities when it comes to granting sick leave, thus rolling back one of the key provisions of relief package

v2.0.

- $200 billion in loans to airlines and other large business concerns affected by COVID-19: Unlike the small business loans, these would not currently be forgivable, but one can easily imagine them becoming so in the future.

What Democrats (and some Republicans) are unhappy about, broadly speaking, is that they think the McConnell bill does vastly too much for corporations and businesses, and not enough for workers. To be specific, some key things that opponents want to see changed:

- Robust Unemployment Insurance: The McConnell plan does relatively little to prop up the

nation's unemployment insurance funding. Given that a record 2.25 million people

filed

for unemployment in the last week, that's a problem.

- Expansion of paid sick leave: Democrats argue, with some justification, that it makes no

sense to liberalize sick leave rules one week, and then tighten them the next. Under the circumstances, more liberal

sick leave rules are what is indicated, they assert.

- Strings Attached to Corporate Money: If the government is going to help multibillion

dollar corporations out, many Democrats want the money to come with significant restrictions (something that was true

with TARP, incidentally). For example, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA)

wants

corporations that take the government's money to be required to commit to a $15/hour minimum wage within a year, to

permanently forego stock buybacks, to accept a three-year moratorium on dividends and executive bonuses, and to promise

to abide by all existing collective bargaining agreements.

- Tax Deadline: Already, the Trump administration has announced that the deadline to pay this year's income taxes will be pushed back by three months. Many members of Congress, on both sides of the aisle, want to see the deadline for filing pushed back three months, as well.

Normally, when Mitch McConnell unveils a bill, he knows he's got the votes in the Senate to get it through that chamber. This time, facing the pressures created by COVID-19, that is clearly not the case. There are some members of his caucus who voted against the $8 billion package, and who surely would vote against a package with a price tag 125 times that. There are other members of his caucus, with Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) an outspoken example, who see eye-to-eye with the Democrats on some things, particularly the need for more robust unemployment insurance. Graham has already lobbied Donald Trump not to throw his support behind the McConnell bill. And then, of course, there's the fact that the House remains under Democratic control, and has no intention of passing a bill that they had no voice in, and that entirely reflects Republican priorities.

In short, this is going to take a while to sort out. That said, the Democrats appear to hold more of the cards here than McConnell does, by virtue of the fact that their ideas appear to have more votes in both chambers than McConnell's do. Further, which of these sounds better to voters: "We couldn't pass a bill that does not give enough relief to workers" or "We couldn't pass a bill that does not give enough relief to corporations"? In other words, the blue team seems to have the more salable argument here. So, expect the final bill to be considerably different from the one McConnell unveiled yesterday. (Z)

Republicans in Denial

When it comes to downplaying the seriousness of COVID-19, Donald Trump, of course, has been the denier-in-chief. The New York Times' David Leonhardt has compiled a list of all the cases where the President has pooh-poohed the pandemic, dating back to late January (beware if you click on the link, though, because it's a long list). And although the President seems to be in "crisis" mode about 80% of the time these days, he's still not there 100% of the time. For example, he's been given "wartime" authority to order industrial concerns to ramp up their production of needed supplies. On Wednesday, he said he planned to invoke that authority immediately. Then, on Thursday, he said he wasn't going to pull the trigger for at least a week or two, and that he's taking a "wait and see" attitude.

Many of the President's closest allies in Congress are, quite clearly, taking their cues from him. We've already noted that Rep. Devin Nunes (R-CA) has been a one-man anti-COVID-19 propaganda machine, offering such opinions as: "One of the things you can do, if you're healthy, you and your family, it's a great time to just go out, go to a local restaurant, likely you can get in, get in easily." He also blamed the whole crisis on the media, who he says are in the pockets of the Democratic Party, and sniffed "The media freaks can do [what] they want."

And Nunes isn't the only one saying things like this. Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI), also a friend of Trump, and one of the handful of Senators who voted against COVID-19 relief bill v2.0, sat for an interview with his hometown Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, and was also dismissive:

I'm not denying what a nasty disease COVID-19 can be, and how it's obviously devastating to somewhere between 1 and 3.4 percent of the population. But that means 97 to 99 percent will get through this and develop immunities and will be able to move beyond this. But we don't shut down our economy because tens of thousands of people die on the highways. It's a risk we accept so we can move about. We don't shut down our economies because tens of thousands of people die from the common flu...getting coronavirus is not a death sentence except for maybe no more than 3.4 percent of our population (and) I think probably far less.

Either the Senator is telling us all that he's very callous, or that he's very bad at math. If we assume a fatality rate of 1% to 3.4% (his numbers), that leaves us with between 3.3 million and 11.1 million Americans dead assuming every American is infected. If only half are infected, cut the numbers in half (between 1.6 and 5.5 million). Even at the low end and 50% infection rate, that is more Americans than have been killed in all of nation's wars combined (about 1.5 million), comparable to the number of Americans who die of all causes in an average year (about 2.8 million), and far, far more than die each year from flu (about 55,000) or traffic accidents (about 36,000).

To take a third example, Rep. Don Young (R-AK) has been exceedingly cavalier about COVID-19, especially for a man who is himself 86 years old. At a recent luncheon, he declared to supporters: "They call it the coronavirus. I call it the beer virus. How do you like that?" and laughed merrily (because Corona is a brand of beer—get it?). "It attacks us senior citizens. I'm one of you. I still say we have to, as a nation and state, go forth with everyday activities," he added.

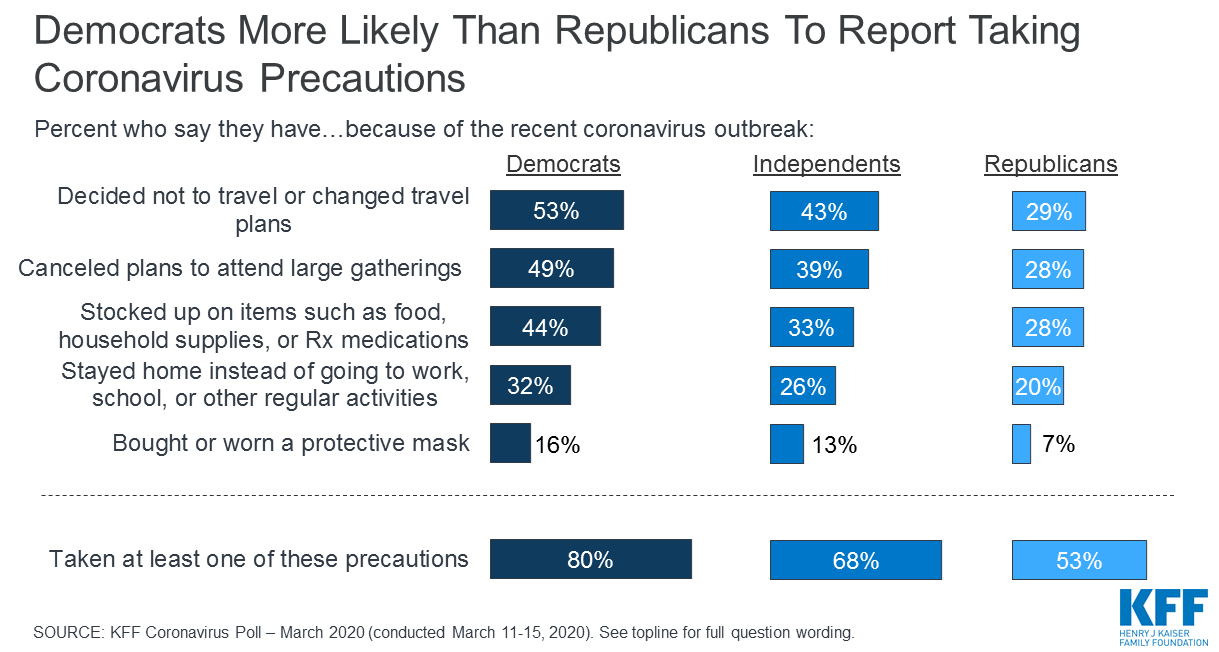

It stands to reason that because these men (and it's interesting that it's almost always men) are leaders, that some people are going to follow their lead. And now, we have hard data suggesting that is exactly the case. This item from Slate runs down some of the polling that's been done, but pretty much the best pollster when it comes to public health questions is the Kaiser Family Foundation. Here is one of the charts they produced after conducting a four-day poll from March 11-15:

As you can see, the difference in responses between Democrats and Republicans is striking. Undoubtedly, not all of this is political—Democrats are more likely to live in cities and states where such measures are being strongly encouraged or mandated—but some of it certainly is. And this poll only considered "substantive" measures that someone might take; one has to imagine Democrats are also more committed to basic, but also harder to measure, things like frequent hand washing and social distancing.

Longer term, it remains to be seen if folks like Nunes, Johnson, Young, and Trump will pay a political price for their blasé attitudes. As we noted in Saturday's Q&A, there's no great historical analogue for this. Perhaps the closest thing is the 1917 declaration of war against Germany. Most members of Congress accepted that it was vital for national security, while others dismissed and downplayed the threat, with 56 of them (50 representatives and 6 senators) voting against the declaration. A majority of those 56 were sent packing by voters at the next available opportunity. (Z)

Trump Has His Scapegoat

Whenever Donald Trump faces a crisis, whether of his own making or not, he generally has a fairly predictable set of responses. He tends to downplay and deny, and to lash out at the media, and to try to blame Hillary Clinton and/or Barack Obama and/or Nancy Pelosi and/or the "deep state." The issue is that none of those scapegoats are present in the White House, and so none is available for him to vent on behind closed doors. Further, and despite his public posturing otherwise, even Trump realizes that his administration does not function perfectly 100% of the time. Since the President never, ever blames himself, he finds some other insider to pin the blame on, and to be his whipping boy (or whipping gal). All three departed Chiefs of Staff have gotten this treatment, as have a number of departed cabinet secretaries and advisers, including Rex Tillerson, James Mattis, Kirstjen Nielsen, Jeff Sessions, John Bolton, and Gary Cohn.

It appears, according to reports from White House insiders, that we have a "winner" in the COVID-19 scapegoat sweepstakes. We're going to run down five possible candidates; see if you can guess which one it actually is. We'll give you the correct answer at the end:

- Candidate 1—Steven Mnuchin

- Rationale: He's been the point person for negotiations with House Democrats, and may have

been too liberal in giving concessions to them. He's also been very frank in admitting the possibility of a recession,

and a sky-high unemployment rate (above 20%).

- Candidate 2—First Son-in-Law/Presidential Adviser Jared Kushner

- Rationale: Presuming to add yet another duty to his vast portfolio, Kushner assumed the

lead in coordinating the White House's response last week, and gave the President bad advice, telling him to treat this

as a P.R. issue and not a medical issue. He also wrote much of the widely panned Oval Office address.

- Candidate 3—HHS Secretary Alex Azar

- Rationale: As HHS Secretary, he should have seen this coming, and should have warned the

administration in time. Also, he's done a mediocre job of leading the response, and in particular coping with the lack

of testing supplies.

- Candidate 4—Rep. Mark Meadows (R-NC)

- Rationale: He was supposed to have taken over as Chief of Staff already, but then he went

and got himself exposed to COVID-19 and had to self-quarantine, so he's been completely unavailable to help, leaving the

President to continuing working with Mick "Already Lost Trump's Confidence" Mulvaney

- Candidate 5—White House Press Secretary Stephanie Grisham and White House Adviser Kellyanne Conway

- Rationale: The tag team of Sarah Huckabee Sanders and Conway was generally pretty good at getting on TV and selling the administration's spin. When it comes to COVID-19, the tag team of Grisham and Conway has proven totally unable to do so.

So, do you have a guess? It is, of course, entirely plausible that Trump is angry with Mnuchin, Kushner, Azar, Meadows, Grisham, and Conway, and that he secretly blames all of them. But the one he's been making a point of targeting, with pretty much anyone and everyone who will listen, is...Kushner. You probably didn't see that one coming, since Trump tends to adhere religiously to Michael Corleone's admonition: "don't ever take sides with anyone against the family." However, according to one of the people who talked to Vanity Fair's Gabriel Sherman: "I have never heard so many people inside the White House openly discuss how pissed Trump is at Jared."

Even before this, there was a fair amount of talk that the Kushners don't much care for Washington, and are eager to return to New York. Could this hasten that process? Maybe so. In any event, when the President is lashing out at his golden boy, it reveals how angry and frightened this COVID-19 situation has made him. (Z)

California Takes the Plunge

The U.S. is about a week behind Europe when it comes to COVID-19 countermeasures. And given that several European nations imposed wide-ranging "shelter-at-home" (or similar) orders last week, it only made sense that we would see that sort of thing make its way across the Atlantic this week. On Thursday, with the federal government still doing a fair bit of flailing around, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) decided to make his move. Expressing concern that more than half the state's population will be infected with COVID-19 in the next eight weeks, he issued a statewide stay-at-home order.

At the moment, the order is somewhat squishy. It defines certain acceptable reasons to leave home (food shopping, to receive healthcare, to head to work if you perform an essential task, etc.), and it's not like California police are stopping people on the streets and asking them to explain themselves. However, now that the country's largest state, with roughly 12% of the entire U.S. population, has gone down this road, surely other states (Washington? New York? Ohio?) will soon follow. And that, in turn, will presumably move the country closer to the point that shelter-at-home becomes considerably less squishy, and considerably more assertive (i.e., martial law). (Z)

Three More NBA Players Test Positive for COVID-19

On Thursday, three more NBA players—the Boston Celtics' Marcus Smart, and two currently unnamed members of the Los Angeles Lakers—tested positive for COVID-19. That brings the total number of NBA players known to have the disease to 14.

Why do we bring this up, given that our focus is politics, and not sports? Well, because the number of known COVID-19 cases in the U.S. is now at 13,000. That is a lot, but is also less than the actual number of COVID-19 cases. There are a lot of reasons that we don't know how many people in the U.S. actually have the disease, but they largely fall into two basic categories:

- Pragmatic: Many sufferers of COVID-19 are asymptomatic or, even if they suspect they have

the virus, are not sure where to go for testing, or have no place to go that is actually equipped and supplied for

testing, or didn't have the money/insurance needed to be tested (though that's not an issue anymore), or have been

tested already and are waiting (up to a week) for results.

- Political: There are some powerful folks in this country (see above) who have decided that their political interests are best served by keeping the number of known COVID-19 cases as low as is possible. "13,000 people have it!" is much less upsetting to voters, they think, than "130,000 people have it!" or "1.3 million people have it!" or "13 million people have it!" As noted, we will presumably discover in November how voters feel about being kept in the dark like this.

Anyhow, back to the NBA. What they are providing us with, right now, are data points. Not the best data points possible, but maybe the best we have right now, since we know the general size of the population of NBA players (about 450) and we know how many have already tested positive (14). That's a rate of 3.1%. If we generalize that to the entire U.S. population, we end up with about 10.2 million infections.

Now, as we said, using the NBA as our data source is far from perfect, because NBA players are not representative of the general population. They travel a lot more, and interact with a lot more people, than the average Joe Palooka. On the other hand, they are also more physically fit than 99.9% of the population (with the corresponding boost in immunity), and it is also the case that some of them haven't actually been tested yet, while others are still waiting for results. So, that 3.1% figure is undoubtedly low.

What it amounts to is this: When choosing whether to believe someone who says "global pandemic!" like Gavin Newsom (see above), as compared to someone who says "much ado about nothing!" like Don Young or Ron Johnson (see further above), the scant data available suggests that this thing is already far more widespread than anyone knows, and that the Gavin Newsoms of the world have the right of it. (Z)

An Asymmetric Presidential Campaign

As we noted yesterday, 2020 could prove to be an asymmetric kind of presidential campaign. Joe Biden, for his part, is likely to be very careful when it comes to holdling large-scale events. First, because he's a good guy, and doesn't want to put anyone at risk. Second, because he's almost 80, and doesn't want to put himself at risk. And third because campaigning via carefully-edited ads and online videos will make costly gaffes much less likely.

Trump, for his part, would like to repeat the 2016 campaign, except nastier. With Biden having effectively locked up the Democratic nomination, Trump 2020 was planning to dip into that vast treasure chest and to unleash an avalanche of negative advertising, in hopes of defining Biden right out of the gate. At the moment, they can't do that, for fear of a backlash. But eventually, those ads will run. Meanwhile, while Biden is likely to play things extra-cautiously, Trump is going to take the show on the road as soon as he thinks he can get away with it. We could have multiple months this summer where Trump is traveling around the country on a regular basis, while Biden is largely sitting at home.

Anyhow, since we happen to have a historian lying around, we thought we would recount the story of the last truly asymmetric presidential campaign, back in 1896. Though it may seem odd to us today, in the 19th century, it was generally considered to be in poor taste for presidential candidates to travel around and ask people for their votes. If you can't believe that, note that when reporters ask politicians if they would like to be vice president, they always demur, saying "there are so many great possibilities around" or "it's up to the nominee." You have no doubt heard 50 politicians say "I would be the best president" but have you ever heard one say "I would be the best vice president"? So was it with the top job in 1896.

Back then, surrogates could campaign, but as to the candidates themselves, begging for votes was seen as beneath the dignity of the office. And so, when a person was nominated for the presidency back then, the expectation was that he would return to his home and wait there as the campaign unfolded. This standard was particularly observed during the Gilded Age (1860s to 1900s).

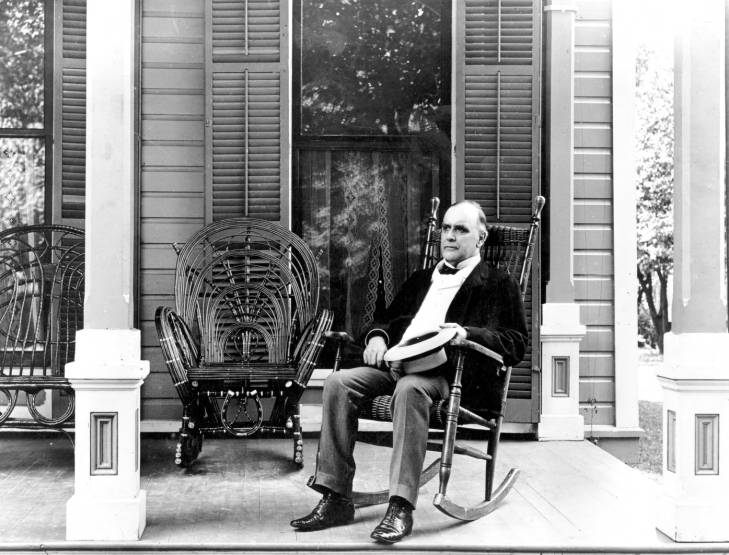

Consequently, when William McKinley received the GOP nomination in 1896, he did what a good presidential candidate was expected to do, and returned home to Canton, OH. For roughly three months, he resided there, as the election season played out. Naturally, someone who is on the precipice of becoming the leader of their country is not likely to be happy sitting and twiddling their thumbs, and doing nothing to aid their chances. And so, like other 19th century candidates, McKinley would get up in the morning and put on a suit, then go out and sit on his front porch:

Just coincidentally, about five minutes after McKinley seated himself, what should happen but a group of Republican dignitaries (mayors, RNC members, members of Congress, prominent businessmen) showing up to pay a visit? Obviously, the would-be president could not be an ungracious host, so he would spend 15 minutes giving the group a little speech, and shaking their hands, and giving them a tour of his house, and (usually) getting a little gift from them:

Once these folks left, a few minutes would pass, and then—surprise!—another group. And then another, and another, and another. In this way, McKinley met and spoke to nearly 700,000 people during that campaign, without ever leaving his front porch. Hence the term "front porch campaign."

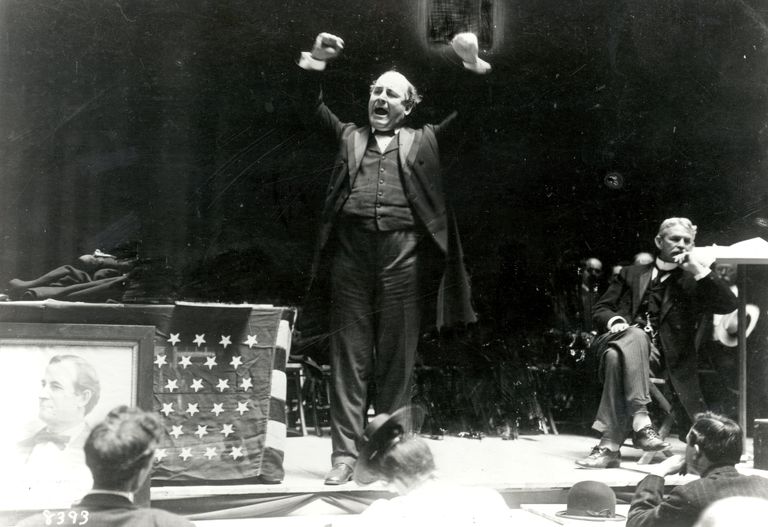

On the other side of the contest, McKinley's Democratic opponent was another William, namely William Jennings Bryan. A front porch campaign was not the right choice for him, for a variety of reasons. To start, he lived in Nebraska, which was (and kinda still is) the middle of nowhere. Further, getting more than half a million people to McKinley's front porch took a lot of planning and cost the Republicans a lot of money. The Democrats of 1896 had neither of those things. Perhaps most importantly, however, Bryan was not great in face-to-face interactions, but he was a gifted speaker. So, he decided to take his message to the American people.

During the campaign, the 36-year-old Bryan worked so hard it's remarkable he didn't give himself a heart attack. He traveled 30,000 miles in the course of less than 100 days, at a time when the only long-distance option available was trains. He also gave speeches by the bushel, sometimes 25 or 30 in a day, and in an era before microphones and amplification had been invented:

His most famous speech of that campaign, and one of the most famous in American history, was the "Cross of Gold," speech which was delivered before the Democratic convention (Bryan was the first person to accept nomination in person). The point of the address was that if you vote against the Democrats/Populists, and their desire to end the gold standard, you are no better than the Romans who crucified Jesus. Republicans were outraged by the insinuation, but the Democratic/Populist crowd at the convention ate it up. At the end of the speech, Bryan got a standing ovation that lasted...48 minutes. (Incidentally, although recording technology was too crude to capture the speech live in 1896, that technology Bryan went into a studio in 1921 and recorded himself reading the text. If you want to hear what his voice sounded like, an audio clip is embedded into the above link, or you can click here).

The upshot is that the candidate put out a staggering amount of energy in 1896, and went largely without sleep for three months. Further, Bryan was doing all of this in a wool suit, mostly in the heat of summer, and before certain essential-to-us personal hygiene products had been invented. And so, he usually had to find a bathroom or other private place several times a day, and give himself a sponge bath in gin, so as to combat odor issues.

Obviously, McKinley is the Biden-like candidate, at least if current circumstances stand, while Bryan is the Trump-like candidate (up to and including the populism, the deployment of religion as a political weapon, and the bald head). It was McKinley who won that election, of course. Still, he was the last person to run a full-on front porch campaign (though Democrat Alton B. Parker and Republican Warren Harding ran partial front porch campaigns in 1904 and 1920, respectively). It's hard to say if this tells us anything about 2020 except, perhaps, that campaigning from home certainly can work. And McKinley didn't even have the Internet, or television, or even radio, at his disposal. (Z)

Gabbard Ends Presidential Bid

Whatever Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) was trying to accomplish by remaining in a presidential primary contest she had no hope of winning, she apparently has accomplished it, because on Thursday she ended her campaign. Interestingly, for someone who supported Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) in 2016, to the point that she resigned her high-ranking post in the DNC in protest of the Party's treatment of him, she endorsed Joe Biden on her way out the door:

I know Vice President Biden and his wife and am grateful to have called his son Beau, who also served in the National Guard, a friend. Although I may not agree with the Vice President on every issue, I know that he has a good heart and is motivated by his love for our country and the American people.

Is this because Gabbard has had a change of heart about Sanders? Or because "Biden supporter" looks a lot better than "Sanders supporter" on a Fox News job application? Or because she aspires to a cabinet post in a hypothetical Biden administration (say, Secretary of Veterans' Affairs)? Could be any of these things, or some other option we're not thinking of.

That was not the only endorsement Biden picked up on Thursday from a formal rival. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY)—remember her?—also jumped on board the S.S. Uncle Joe with this tweet:

I’m proud to endorse @JoeBiden today. Our country needs a president who will provide steady, honest leadership, and I believe Joe has the right experience, empathy, and character to lead. I’m excited to help him defeat Donald Trump in November.

— Kirsten Gillibrand (@SenGillibrand) March 19, 2020

We have no idea how much influence she has, but she did make women's issues the centerpiece of her campaign, and she did hit Biden on that subject a few times during the debates. So, her words might have some weight with women who had doubts about the former veep.

This means that, of all the former Democratic candidates who have endorsed so far, all but Marianne Williamson has gone for Biden. The biggest holdout, at this point, is Elizabeth Warren, who could go for Sanders because she is a progressive, but who could also go for Biden because she is a pragmatist and because she doesn't actually like Sanders all that much anymore. She was asked on Thursday about her endorsement plans, and said: "I think Bernie needs space to decide what he wants to do next, and he should be given the space to do that." Translation: "I would prefer not to choose, and would like Sanders to make the choice for me by dropping out." Given that if ever Sanders needed her endorsement, it's right now, that presumably means that the only two options Warren is considering are: (1) endorse Biden, or (2) endorse nobody. We will learn soon if Sanders decides to take the hint, or instead decides to stick around. Thus far this week, he's been unwilling to answer questions about his campaign's future, telling reporters "You have to stop with this. I'm dealing with a fu**ing global crisis." It used to be that politicians did not use such language in public, but that was in the years B.T. (Before Trump). (Z)

Back to the main page