Saturday Q&A

This mailbag is about as heavy on history questions as any has ever been. It is very fortunate that Civil War historians are universally renowned—idolized, even—for their knowledge, their wisdom, and their insight.

Q: Not following the George Floyd trial as closely as a friend of mine, I wrote him and said, "It

is impossible for a white policeman to be convicted of killing a black man in America."

I would love to be proven wrong. Especially by the outcome of this trial. But my favorite website may already have the

answer: Has a white cop ever been convicted of murdering a black man in the United States?

B.C., Walpole, ME

A: There is something to be said for the racial dimension to your question; juries have historically been more willing to trust white people in a courtroom (whether as witnesses, plaintiffs, or defendants) and less willing to trust people of color. However, the main dynamic here is that it is nearly impossible for a policeman of any sort to be convicted of killing anyone in America.

There are several major reasons why a murder/manslaughter case against a police officer is difficult to make. Here are three of the biggies:

- Benefit of the Doubt: Juries tend to begin with the presumption that police officers are

trustworthy public servants who put themselves in harm's way for the greater good of the American public. So, jurors are

generally loath to substitute their judgment for that of the officer(s).

- Lack of Evidence: Since most officer-involved killings take place in the line of duty, the

question is not whether they did the deed, but whether their reaction was justified. This gets into questions about the

extent of the provocation and the officer's state of mind. The only folks who can speak to these issues, generally, are

fellow officers. And fellow officers are reluctant to testify against one of their own.

- Available Defenses: There are also some pretty effective defenses available, in most cases. If the victim had a weapon, an argument of self-defense almost always works. If the victim did not have a weapon, an officer can still save themselves by arguing that what they did was consistent with the training they received and with department policy. The latter issue has been a major focal point of the Floyd trial.

For these reasons, officer-involved shootings are rarely charged, much less punished. In the 15 years prior to the Floyd trial, charges were only brought 110 times, for an average of about seven a year. Of those, only five resulted in a murder conviction. However, one of those five did involve a white officer killing a black victim: Jason Van Dyke's murder of Laquan McDonald. So, your statement to your friend, while substantially correct, is not entirely accurate.

Q: If the filibuster for statehood was neutralized, how fast could D.C. achieve statehood? How soon could their new senators and representatives be seated? K.H., Albuquerque, NM

A: H.R. 51 has already been passed by previous House delegations, and it has been reintroduced by Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) this term. In theory, it could be passed by both chambers in a day. However, such bills tend to create a probationary period of about 6 months in order to give the new state time to hold elections. For example, the Hawaii statehood bill became law on March 18, 1959, but Hawaii was not formally admitted until August 21, 1959. The same consideration would presumably be extended to D.C., though if there were a real rush, they might be able to chop it to maybe 3 months. It would be hard to hold both primaries and a general election any more rapidly than that.

Q: What's the pathway for Democrats to pass D.C. statehood in the Senate? Budget reconciliation won't work and Republican votes are a non-starter. Do they have any other options other than filibuster reform and 50+1 Democratic votes? Is there any reason to think any Democrats (cough, Sen. Joe Manchin, D-WV, cough, cough, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-AZ) would not vote for it? S.S., West Hollywood, CA

A: You never know what can be snuck by through reconciliation until you ask, and it's at least plausible that D.C. statehood could be fashioned into something that has budgetary impact, though (Z) is more persuaded of the potential viability of this than (V) is. But, of course, the only person who matters here is (E. MacD.).

Beyond that, if we're talking about going scorched earth, then Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) could wait until two Republican senators are absent, and eliminate the filibuster for statehood votes with 49+1 Democratic votes, even if Manchin crossed the aisle. However, this sort of quorum trickery is not common, and usually only happens when it appears very well justified (such as what happened when the Democrats outmaneuvered Sen. Ron Johnson, R-WI, in response to his time-wasting efforts meant to slow down passage of the COVID-19 bill).

Failing these two possibilities, then Schumer is just going to have to get his whole caucus on board with either eliminating or further restricting the filibuster. Manchin, for his part, has expressed support for D.C. statehood, while Sinema has avoided answering that question. In any event, they would both lose leverage if they were no longer the "swing" senators, so no matter what they do or don't say, we can't be sure of their true feelings until the rubber hits the road and they are forced to cast a vote.

Q: You have written about the Senate Majority Leader, and noted that the job didn't even exist until about 100 years ago. Can you confirm my assumption by extension that the position of Senate Minority Leader didn't exist at that time, either? Back when this/these position(s) didn't exist, how was the agenda in the Senate set? P.F., Wixom, MI

A: You're correct. The two party caucuses in the Senate did not start formally electing leaders until the early 20th century, meaning there was no official majority or minority leader before then.

This statement implies an answer to the rest of the question. Before there were formally elected official party leaders, the Senate was run by unofficial party leaders who rose to command of their caucuses through political skill, force of will, etc. John C. Calhoun (D-SC), Roscoe Conkling (R-NY), and James G. Blaine (R-ME) all acted as de facto majority leaders at various times, setting the agenda of the Senate and running its business, even if they did not have a formal title that enabled them to do so.

Q: With reference to your item about Michele Bachmann demanding a particular committee seat: Why the heck do members of Congress put up with a seniority system for getting on influential committees? In other words, why should one state have less power in the country than another just because they want to change who represents them? It can't be in the Constitution. You have written many times that it takes decades to have any influence in the Senate because of that. It always sounded to me like a system that was undemocratic, un-American and extremely unfair to the voters of individual states. D.E., Austin, TX

A: There are two primary reasons. The first is that committee service, particularly today, and particularly on the really important committees, requires the development of fairly extensive expertise. You don't want someone running the Senate Finance Committee, for example, until they have a really strong command of the nuances and subtleties of applied macroeconomics.

The second reason is: What is the alternative? In the 19th century, plum committee assignments were essentially patronage positions that went to the favored friends and allies of party leaders. If you were a member of Congress, wouldn't you prefer to be rewarded for your service, as opposed to your ability to kiss up to the pooh-bahs?

Q: Can you tell us more about how the Senate parliamentarian is selected? How old is the current one? Ostensibly a neutral position, is there political vetting by whoever gets to nominate him/her? B.R., Portland, OR

A: The Office of the Senate Parliamentarian was established in 1935. Before that, questions about parliamentary procedure were handled by the members themselves, in consultation with their staffs and with the Secretary of the Senate. The six people who have served as Senate Parliamentarian since the office was created all worked in various non-partisan jobs in Washington, often involving legislative record-keeping (for example, helping edit the Congressional Record), then took jobs as assistant parliamentarians before being promoted to the head job. The only slight exception is the first Senate Parliamentarian, Charles L. Watkins, who could not have worked as an assistant parliamentarian first (since the office didn't exist), but who served in a similar role for many years, as assistant to the Secretary of the Senate with a focus on floor procedure.

The Parliamentarian is chosen by the sitting majority leader, and then approved by the Senate. It is a civil service position, and so the politics of the candidate aren't relevant, and usually aren't known. They are chosen based on competence, something that is very plausible for the senators to evaluate, since they work with the assistant parliamentarians on a regular basis. The current parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, worked in the Senate library and as an editor of the Congressional Record before earning her law degree and then joining the Senate Parliamentarian's office in 1999, earning promotion to senior assistant parliamentarian in 2002, and then being elevated to the head job by then-Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) in 2012. MacDonough is 55 years old. For what it is worth, her immediate predecessor, Alan Frumin, served until he was 65.

Q: Could (Z) recommend a book or two on the history of Congress? L.R.H., Oakland, CA

A: There are different kinds of books that might be of interest, so you're going to get four recommendations.

If what you want is an overview of the history and development of the Congress, then consider America`s Congress: Actions in the Public Sphere, James Madison Through Newt Gingrich, by David Mayhew. It's true that the book does not include the last generation or so, since it ends in the early 2000s, but it manages to do a pretty good job in workmanlike fashion (less than 300 pages).

If you would like a book that exposes you to different viewpoints on different issues, allowing you to choose which you'd like to read, then you will want The American Congress: The Building of Democracy, edited by Julian Zelizer, which has essays on 40 different subjects from leading Congressional scholars, grouped into four broad historical eras.

If you want an interesting read that also gives some insight into the development and dynamics of Congress (without that being the entire focus), then you might like The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War by Joanne Freeman.

If you want a case study of congressional operation in action, then you can't do much better than Master Of The Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson by Robert A. Caro.

Q: Because of COVID-19, a lot of companies are re-evaluating their work-from-home policies. My company, for one, always insisted that most employees had to work out of one of our offices, which are generally located in urban centers. Having successfully transitioned to a work-from-home model, however, we are now being given the option of working from home, even after the offices reopen. As a result, some of my coworkers, the majority of whom are Democrats, are planning to move away from the Boston area. Do you think these kinds of moves will be common enough that they could have an effect on the distribution of Democrats and Republicans throughout the country? Could this significantly alter the makeup of congressional districts that traditionally have been solidly red or blue? A.T., Arlington, TX

A: Even before the pandemic, there were articles being written about the shift of people from (expensive) blue cities to (less expensive) red suburbs and cities. That trend is surely going to accelerate, given increased reliance on work-at-home. It will take a while before we know if it's enough to flip whole states, or a meaningful number of congressional districts, but that outcome is certainly a possibility.

Q: Which state currently has the most liberal voting laws (those that make it easy to vote)? Is there a website that has information for all fifty states and/or one that tracks state legislation on this issue? J.L., Baltimore, MD

A: Well, the states where it is easiest to vote are surely the ones that have universal vote by mail. There are five of those: Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington. All five automatically send ballots to all eligible voters. Hard to see how it could be much more liberal than that.

Lots of sites track the voting setups of the various states. The U.S. Vote Foundation has a very nice one-page overview of voting options in the 50 states, D.C., and the overseas territories. As to legislative developments, the Brennan Center produces a monthly report; here is the latest edition. You can sign up for their e-mail list, and they'll send you a link when updates are released.

Q: Although the legislature had enough votes for a supermajority to override Gov. Asa Hutchison's (R-AR) veto of the transmisic bill in Arkansas, it was noted that it only requires a simple majority in each of their legislative chambers. It seems to me that makes the governor fairly impotent in the process of writing laws. I checked for Washington state, where I live, and our state constitution requires a 2/3 majority in both chambers. Is a larger majority for veto overrides the norm in most states? Is there any history as to why some states didn't follow the U.S. Constitution for veto overrides? R.G.E., Mukilteo, WA

A: There are 36 states where a 2/3 majority of both houses is required for an override. There are seven states where a 3/5 majority of both houses (or of the single chamber, in Nebraska's case) is required for an override: Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio, and Rhode Island. There are six states where a majority vote of both chambers is needed for an override: Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia. And finally, in Alaska, the two chambers of the legislature meet in joint session to consider veto overrides, and 2/3 of that joint session (regardless of which chamber they come from) must vote in favor of an override.

There are actually significant variances between the states when you get down into the weeds, and those are usually a product of: (1) the local sense of what's best, and (2) political maneuvering. For example, North Carolina—reflecting the traditional Southern dislike of centralized power—didn't have a gubernatorial veto at all until 1996. Or, to take another example, the legislatures of Alaska and Arizona wanted to raise the bar for raising taxes. So, they changed the rules such that if a governor vetoes a tax bill, it takes a three-fourths vote for an override, instead of the two-thirds normally required in those states.

Q: You noted that Mayor Tishaura Jones (D-St. Louis) might challenge Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) in 2024, or pursue that open Senate seat if Hawley vacates it to run for president. I recall reading that before the 1960 election cycle Lyndon Johnson was able to secure a change in Texas state law that enabled him to run for reelection to his Senate seat while also running for president. Apparently, Missouri doesn't have a "Lyndon law" (as they came to be called) on the books. How common are such laws in our current politico-legal context? J.B., Ingleside, IL

A: "Lyndon Law" is the slang term (though an outdated one, since the original Lyndon Law is no longer on the books), while the more formal term is "dual candidacy" law. In any event, there are five states that definitely allow a person to run for federal executive office (president/VP) and federal legislative office (House/Senate) at the same time: New Jersey, Massachusetts, Ohio, West Virginia, and Hawaii. Further, California law is a little hazy, such that a dual run is technically legal, even if not in the spirit of the law (the statute says a candidate may not "file" statements of candidacy for multiple offices, but president/VP don't actually require that filing, and so those two jobs are technically not covered). In states other than those six, candidates have to make a choice between federal offices.

All of this said, it is also possible to run for one office, give up, and shift gears to another. That happened with Sen. John Hickenlooper (D-CO) during the 2020 cycle and Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) during the 2016 cycle. Further, it is not uncommon for state legislatures, if they are friendly to the candidate, to tweak the rules or to grant a waiver when the situation arises. This happened with Joe Lieberman in 2000, Joe Biden in 2008, and Paul Ryan in 2012.

Q: Your item about Rep. Matt Gaetz's (R-FL) request for a blanket pardon before the former guy left office got me thinking about the concept of "pocket" or "secret" pardons. If pardons can be issued in secret, only to be disclosed if and when needed, what is to prevent a former president from concocting a new "pardon" after leaving office and proclaiming that it was a secret pardon issued before leaving office? That would be, in effect, a forgery of a pardon. But who would know, and what would stop someone from getting away with it? D.C., Sarasota, FL

A: Presidential pardons are processed and registered by the Dept. of Justice's Office of the Pardon Attorney. On their website, you can check on the status of clemency requests, and download the pardon warrants for those who have been given them. For example, here is Roger Stone's pardon.

If a president wants a pardon kept "secret," he can order the DoJ not to publish the warrant (or the information) on their website, although they would have to reveal it in response to a Freedom of Information Act request if someone thought to make one. If a president wants to circumvent the DoJ and the Office of the Pardon Attorney entirely, and hand the pardon directly to the recipient, he could legally do so, but it would be highly irregular, and it would raise all kinds of red flags if the pardon "appeared" after that president left office. In that case, the pardonee better have some sort of proof they received the pardon warrant prior to the end of the president's term.

Q: Considering the $2,900 donation limit to a candidate, shouldn't WinRed (or the Trump campaign) be in violation of some campaign finance law by intentionally soliciting more than that from an individual donor? For instance, if someone gave $500 in September and was enrolled in weekly recurring money bombs, the grand total of that transaction would be $4,000-$5,000. It's one thing if a donor inadvertently gives above the limit, but in this case the campaign/platform created the scenario for the excess donations. R.M., New York, NY

A: Well, it's not illegal to collect the money. It's just illegal to keep it once the overage has been discovered. As a "tycoon" (of sorts), Donald Trump learned long ago that if you get to collect interest on someone else's money for a few weeks before you give it back, that's still a few weeks of free interest payments.

Further, the Trump campaign was pretty brazen about bending the rules to the breaking point. The donation limit is $2,900, but that is per election. So, if the Trump campaign collects $5,000 from someone in the month of September, it can credit $2,900 to the primaries and $2,100 to the general election and all is well, as long as the person didn't otherwise donate. Further, Trump 2020 might have redirected some of the money to the RNC or to his super PAC; it's not yet clear.

Q: What do you think of the practice of deplatforming and do you think it works at stopping its

targets? I support the deplatforming of Donald Trump from social media but I do not think it will be successful in the

long run at stopping his influence in the country. The reason why is what has happened with other deplatformed speech.

Child pornography is banned from all reputable social media sites, people who advocate child abuse are banned from

social media, and child porn is illegal everywhere I know of. However, it is still available on the Internet and it is often

shared through encrypted methods. Deplatforming it hasn't stopped it but it pushed it into underground websites that

are difficult to monitor and control.

If deplatforming Donald Trump doesn't work, what can be done to prevent him from inciting another riot?

R.M.S., Lebanon, CT

A: To start, just because something is not eliminated entirely does not mean it has not been severely curtailed. There may still be illegal porn out there, but it's far less than the amount there would be if child porn were not illegal, or if the laws were not strongly enforced (backed by buy-in from private interests). The same applies to Donald Trump; his power to command the masses is much reduced since he no longer has social media and he no longer has the bully pulpit of the presidency. Yes, he can hold rallies, but those are not an effective way to whip millions into a lather (thousands maybe, but not millions). He can go on right-wing news channels, but those have a limited reach, and they aren't going to let Trump go too far for fear of exposing themselves to liability. He can have Trump Jr. tweet, but if Trump Jr. pushes it too far, then he'll get booted off of Twitter, too.

Also, don't underestimate the extent to which social stigma also serves to limit child pornography. Getting caught with such materials—heck, just being accused of having it—turns a person into an instant social pariah. Similarly, Trump's greatest vulnerability when it comes to the love and adoration of his followers, may be the E. Jean Carroll and Summer Zervos cases. The Trumpers clearly have a high tolerance for lying, grift, bigotry, etc. But they've shown considerably less tolerance for sexual misconduct. Look what happened to Roy Moore, or what is currently happening to Matt Gaetz. Recall that the one and only time that Trump apologized publicly was after the pu**y grabbing tape. If there is a clear finding that he raped or assaulted Carroll, Zervos, or someone else, then that could be the final "deplatforming" for him.

Q: I wasn't going to ask, hoping the Trumps were in the rearview mirror, but since you brought it up, what is it about Eric Trump that he seems to be the brunt of a lot of "he's so stupid" jokes? Don Jr. seem to be in the spotlight much more and has said and done a lot of really stupid stuff, so why does Eric get the "business" all the time (from this site, as well as others, including late-night comics). D.D., Hollywood, FL

A: We would guess there are three things in play here. First, Barron Trump was/is off limits because he's a minor. Tiffany Trump was/is mostly off limits too, because she's pretty young and because she's not really in the family orbit that much. Don Jr. quickly acquired a reputation as a hothead and a loose cannon, and that's been his public image since. Ivanka quickly acquired a reputation as an out-of-touch rich snob (think: Marie Antoinette), and that's her public image since. Eric was really the only one available to be the "dumb one," and since he's lower profile, it was easy to project that on to him.

Second, Eric just looks kinda dopey, particularly in pictures taken when he was younger. This is not fair, and it's not a sound basis for judgment of his intellectual capacity, but in a world where memes are king, life is often unfair:

Third, don't underestimate the awesome power of Saturday Night Live to define a political figure's public image. They persuaded Americans that Gerald Ford was a clumsy fool, that George H. W. Bush was a wimp, and that Sarah Palin was a few cards shy of a full deck. With the Trump brothers, Mikey Day played Don Jr. as a conniving mastermind and Alex Moffatt played Eric as a childlike moron who often says out loud what he's not supposed to say. It was quite effective.

All of this said, we made the joke we did because "Donald Trump Jr." didn't work in terms of the rhythm of the line. If it had, he would have been a better choice, since the line was about the shady sorts of folks Trump Sr. associates with.

Q: I was intrigued by this statement on Friday: "in our academic work, we generally start with a

premise and then look for evidence to support that premise. That is particularly true for a historian, like (Z)."

Perhaps you can elaborate. I would have thought that the most sound approach would be to look at the facts (which might

suggest a premise), then articulate that hypothesis (premise), then test that hypothesis by a more thorough study of the

facts. If you start with premise, and then look for facts to support it, aren't you in danger of ignoring the facts that

contradict it?

Perhaps the next step in your methodology is "and then we see how strong our theory is when it is presented to our

critical and well-educated colleagues."

J.B., Bend, OR

A: It's true, the academic process is a bit more complex and nuanced than could be communicated in a brief paragraph. A person spends their undergrad and early grad careers being exposed to factual information. And they spend their entire grad careers being exposed to what other scholars have done with the information, including what questions those scholars have asked and what conclusions they have reached. So, by the time a historian (or any other sort of scholar) starts doing their own work, they have some idea of what range of possible interpretations is supported by the evidence, and can be explored with the available tools and sources. In other words, it is a cycle of evidence → premise → more evidence → refined/revised premise → more evidence → etc.

Needless to say, if the evidence points in a direction other than the one you originally expected, you have to adapt. More than once, (Z) started with one argument and ended up with the opposite argument after further study. Also, there is much wisdom in discussing examples that run contrary to one's thesis, and explaining why they don't completely undermine the thesis. That puts you in a better position when, as you note, you submit your work to other scholars for their critical assessment.

Note also that there are some folks who call themselves historians, and who start with a thesis and are determined to prove it, no matter what crimes they have to commit against the evidence or professional ethics. In the Civil War field, this includes books that argue that Abraham Lincoln was gay, or that there were large numbers of Black soldiers in the Confederate Army. However, these works are rarely produced by trained historians, and are ignored by scholars in any event.

Q: The ACLU sent me a renewal reminder, and along with it came a pocket-size booklet containing the U.S. Constitution. Being short on reading material during lunch, I opened it up and randomly went to Article VII. There were two paragraphs. The first was as straight-forward, understandable and reasonable as could be. The second...well, look:

The Word, "the," being interlined between the seventh and eighth Lines of the first Page, The Word "Thirty" being partly written on an Erazure in the fifteenth Line of the first Page, The Words "is tried" being interlined between the thirty second and thirty third Lines of the first Page and the Word "the" being interlined between the forty third and forty fourth Lines of the second Page.

Four questions (and not just because it's Passover): (1) OK, I understand they didn't have Microsoft Word or even vi, but why didn't they just re-write the whole thing. It's not that long. They could have paid someone to do it; (2) Does this passage mean anything? Does anyone know what it means?; (3) The paragraph doesn't even consist of sentences, just fragments. What the farrago?; and (4) If this paragraph is truly gibberish, is the whole document null and void? Are we then still living under the Articles of Confederation? D.A., Brooklyn, NY

A: Most readers will have had the experience of writing a check, making a small error, and being asked to initial the correction to verify it's legitimate. That's pretty much what is going on here.

The passage you've noted, which is the second and final portion of Article VII is sometimes known as the "typos clause." It's a listing of the corrections Jacob Shallus made as he noticed errors in his transcription of the document, and an affirmation that those corrections are legitimate and are not post facto. In other words, he's saying (in shorthand): "I really did add "is tried" to the document; that wasn't someone else" (to take one example). English spelling was not yet standardized at that time, so his inventive spelling of "erasure" is not unusual.

The reason that the document was not rewritten is that producing a document of that length, using a quill pen, and making zero errors is no small feat. Further, the framers wanted to promulgate the Constitution as rapidly as possible, in hopes of forestalling as much resistance as was possible, and so time was of the essence. A new draft would have taken 2-3 days, and if that one was not perfect, then 2-3 more, and so on. Further, given that time, ink, and parchment were all valuable commodities back then, this was an entirely acceptable and "formal" way of amending any legal document, and would have been familiar to any reader in 1787, just like the initials on the checks today.

There are a couple of reasons that most people are unaware of this little footnote (for lack of a better word). The first is that few people bother to actually read the Constitution. The second is that most copies of the Constitution actually omit the typos clause, reasoning that the rest of the document is instructions on how to govern a nation, while that clause is just instructions on how to properly read that particular piece of paper.

Q: I'm hoping the resident historian can help me identify an article I remember reading.

Several years ago, well before Donald Trump, and perhaps shortly after the Sandy Hook shooting when gun control was still a topic

worth discussing in this country, I read a long article by an actual historian about the origins of the Second

Amendment. I remember it talked about the fear white people in the South had of a slave rebellion and how the Second was a

lot about that. I also remember it saying that whites in power at that time were happy to support democracy so long as

it kept them in power, but they were also very happy to jettison it and use any means necessary, "up to and including

murder,' to preserve power.

That is all the specific details I remember. Any idea what article I am talking about?

B.J., Boston, MA

A: Probably can't get you to the exact article, because that argument has been around for close to 200 years, and so there are many articles that advance it. That said, the foremost advocate for that position these days is Saul T. Cornell, who is currently a history professor at Fordham, and who used to be the Director of the Second Amendment Research Center at Ohio State. Here is a recent article he wrote on this subject (albeit not a long one); you could also look at his book Whose Right to Bear Arms Did the Second Amendment Mean to Protect?. Hopefully this gets you in the ballpark of what you're looking for.

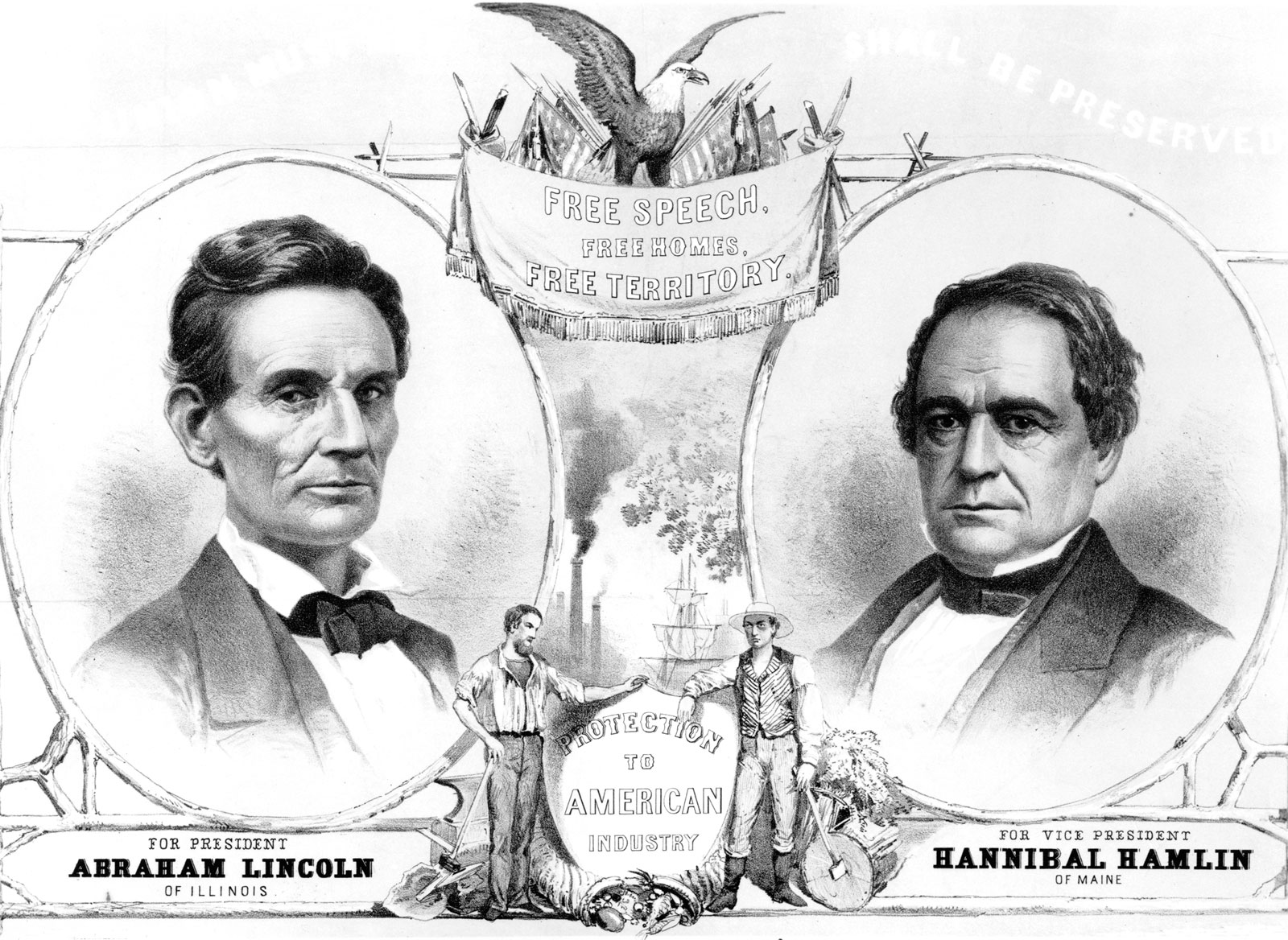

Q: I have often wondered about how the Republican Party became so closely intertwined with big business. I had assumed that was part of a natural outgrowth of it being a political party based in the North, such that they became mutual allies once the Civil War and Reconstruction ended. But your item on Tuesday said that "since the day the Republican Party was founded in 1854, it has been pro-big business." That caught me by surprise since I have always conceived of 1850s Republicanism to be primarily a one-issue party (abolition) that matured into the modern party it is today. Could you expand on what stands the pre-Civil War party took that so closely aligned them with big business from the start? S.H., Phnom Penh, Cambodia

A: The Republicans were never a one-issue party. When they emerged in 1854, they tried to unify as many interest groups as was possible in order to be able to challenge the well-established Democratic Party. That included abolitionists ("get rid of slavery!"), free soilers ("keep slavery from expanding!"), nativists, western farmers, and non-immigrant laborers. The single-biggest faction was former Whigs (since the Whig Party had just collapsed), and the Whigs had been the pro-business/pro-industry party for multiple decades.

Take a look at this Lincoln poster from the Election of 1860. It doesn't say anything about slavery, since that was a touchy issue for some, and the Republican Party was the only game in town for anti-slavery voters anyhow. You will note the smokestack featured in the background, and the slogan featured prominently in the bottom foreground:

Q: I notice that you referred to the U.S. becoming an industrialized world power after the Civil War. I knew that, but here's a question for a historian: What do you think was the major event or discovery or innovation that tipped the scales for the United States to become a major world power? S.B., New Castle, DE

A: Railroads. Compared to the industrial powers of Europe, the U.S. had significant advantages, including much more land, many more resources and, by the mid-19th century, many more people. However, it was hard to properly harness all of those advantages with only horse-powered transportation (which was slow, and unreliable over long distances). Rivers could be used for some purposes, but only served areas that were, well, close to a river.

The advent of railroads in the 1830s and 1840s allowed the nation to fully take advantage of its abundant national resources (including all the gold and silver and other precious commodities found out West), and to develop a national market for goods. Trains also made possible the war that added California and much of the Southwest to the U.S. (the Mexican-American War), facilitated the successful subjugation of the Native Americans, and allowed the Union government to defeat the Confederacy.

Q: Twice in the last week you've mentioned offhand that the U.S. began its "empire building" in 1898, after the Spanish-American War. But wouldn't it be more correct to say "overseas empire building"? The U.S. began building an empire at its founding, taking over and settling a vast region of North America between the Atlantic and the Pacific that was once occupied by Native Americans. In other words, "Manifest Destiny" is the same thing as "empire building," but has a more triumphalist and justificatory ring to it for the settlers. P.R., Kirksille, MO

A: Because the wars against the Natives, and the expansion of the U.S. into a holder of overseas territories are different in some significant ways, most historians would be uncomfortable subsuming them under the same term. Almost always, the wars against the Natives are seen as part of "the conquering of the West," and the Spanish-American War is seen as the first chapter in the development of the American empire. That said, there are some outspoken leftists who parallel the two processes much more aggressively, like Howard Zinn (RIP). That said, even he distinguishes between the "internal" empire and the "external" one.

Q: The final two sentences

in the item

about Biden and guns got me thinking about the end of

the republic: "That firearm you buy today could very well be in perfect working order for the 500th birthday of the

United States in 2276. Heck, the gun might be more likely to make it to that date than the country."

The American democratic experiment has lasted nearly 250 years. As a thought exercise, what are the most likely

reasons for the USA not existing in 2276 AD? A worse pandemic? A successful insurrection or coup? A Civil War-like

secession of some states or regions? Some sort of nuclear or major cyber attack? An asteroid? The My Pillow Guy being

right all along?

J.F., Toledo, OH

A: Two centuries is a long time, and so many things could happen. However, we can see three basic scenarios where the U.S., as we know it, comes to an end. The first is that, fraught with internal tensions, it breaks apart into smaller pieces. The second is that its military power declines at the same time that rivals' power increases, and it is somehow invaded and conquered by China or some other unfriendly superpower. The third is the Star Trek scenario; the world decides that unity is preferable to competition, and forms a one-world government.

If you wish to contact us, please use one of these addresses. For the first two, please include your initials and city.

- questions@electoral-vote.com For questions about politics, civics, history, etc. to be answered on a Saturday

- comments@electoral-vote.com For "letters to the editor" for possible publication on a Sunday

- corrections@electoral-vote.com To tell us about typos or factual errors we should fix

- items@electoral-vote.com For general suggestions, ideas, etc.

To download a poster about the site to hang up, please click here.

Email a link to a friend or share:

---The Votemaster and Zenger

Apr09 What Is Going on with Joe Manchin?

Apr09 Whither the Democrats?

Apr09 New York Governor's Race Apparently Has Two Candidates in the Trump Lane

Apr09 I Did Not Have Sexual Relations with that Woman

Apr09 COVID Diaries: Why so Serious?

Apr08 Biden Will Announce Executive Action on Guns Today

Apr08 First Georgia, Now Texas

Apr08 But Not Kentucky

Apr08 Boehner Blames Trump for the Capitol Riot

Apr08 Republicans Get a Deadline on the Infrastructure Bill

Apr08 D.C. Statehood Bill Will Come Up This Month

Apr08 Why Don't Republicans Hate Kamala Harris?

Apr08 Marjorie Taylor Greene Is Raking in the Big Bucks

Apr08 So Is Mark Kelly

Apr07 Biden Administration Says It Won't Get Involved in Vaccine Passports

Apr07 California Set to Reopen

Apr07 DCCC Will Play it Pretty Safe in 2022

Apr07 Alcee Hastings Is Dead

Apr07 Gaetz the Latest to Learn that Loyalty to the Trumps Is a One-Way Street

Apr07 Fear of a Black Planet

Apr07 St. Louis Has a New Mayor

Apr06 Good News, Bad News for Biden on the Infrastructure Bill

Apr06 Fauci Concedes What Everyone Should Already Have Known

Apr06 Whither the GOP, Part I: Corporate America

Apr06 Whither the GOP, Part II: The Religious Right

Apr06 Whither the GOP, Part III: The Right-Wing Media

Apr06 Putin Apparently Isn't Going Anywhere

Apr05 Battle of the Bridges Begins

Apr05 Maybe the Georgia Law Isn't As Bad as Feared

Apr05 Other States Are Watching What Happens in Georgia

Apr05 Biden's Infrastructure Plan May Hurt Unions

Apr05 The Old White Guy Is More Progressive than the Young Black Guy

Apr05 Thanks, but No Thanks

Apr05 Trump Scammed His Supporters

Apr05 Private Property Is Socialism

Apr04 Sunday Mailbag

Apr03 The First Shoe Drops...But What Will Follow?

Apr03 Saturday Q&A

Apr02 Let the Games Begin

Apr02 Gaetz' Troubles Mount

Apr02 Democrats Hope Johnson Breaks His Word

Apr02 Past as Prologue, Part II: Midterm Elections and the House

Apr02 Guess It Kinda Worked Out, After All

Apr02 COVID Diaries: No Light at the End of the Tunnel

Apr01 Biden Unveils His Big Plan

Apr01 Biden Won't Ask for a Wealth Tax

Apr01 No Gas Tax or Mileage Tax, Either

Apr01 Democrats Are Arguing about H.R. 1

Apr01 EPA Starts the DeTrumpification of Its Scientific Panels