|

|

The Danger of Domestic Fanaticisms Trump Still Lost Impeachment Trial Sharpens GOP Divides |

White House Press Aide Resigns Cassidy Censured for His Impeachment Vote Raskin Defends No Witnesses Call |

• Saturday Q&A

The Defense Rests

Donald Trump's lawyers put up their defense on Friday. They used only 3 hours of the 16 they have been allotted. Whether that is because they knew it was not necessary to expend their full time, or because that gave them less time to screw up, or because their client has a very short attention span, only they know.

As expected, the defense they mounted was a hodgepodge of different ideas, primarily tailored for an audience of one. Here are the main elements of their presentation:

- Cancel Culture: Michael T. van der Veen, making his first appearance for Trump during

these proceedings, kept a straight face as he made the argument that Trump is a victim here. According to van der Veen,

he is also a victim in the Georgia election fraud situation and the "good people on both sides" situation in

Charlottesville. Poor guy.

- Ignorance: Responding to claims that Trump (metaphorically) fiddled while Washington

(metaphorically) burned, van der Veen said the then-president had absolutely no idea that things had gotten violent at

the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue. This despite the fact that Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-AL), one of the Trumpiest

members of the Senate, said The Donald certainly did know.

- Whataboutism: The defense also showed

an 11-minute video

in which they had edited together dozens of clips of Democrats using incendiary language, particularly the word "fight,"

which appears 238 times:

In other words, it doesn't matter if you say it while sitting on a couch on the set of the Ellen DeGeneres show, or while addressing a large, angry, armed crowd—it's precisely the same. Incidentally, van der Veen made the point that his video is not an example of whataboutism. We will leave it to readers to decide for themselves what it means if your rhetorical technique is so obvious that you need to offer a disclaimer. - Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire: Trump's lawyers also brought copies of some of the videos shown

by the House impeachment managers, interspersed with comments and additional footage explaining what "really" happened.

They accused the Democrats of grossly distorting the truth.

- There was no insurrection: And speaking of distorting the truth, the defense also decreed that what happened wasn't an insurrection, and even if it was, it could not possibly have been triggered by Trump's verbiage. They also claimed, at various times, that an Antifa leader was arrested at the Capitol on Jan. 6 (not true), that Trump's first tweet during the insurrection was a call for peace (actually, it was an attack on Mike Pence), and that Trump hates violence of any sort (uh, huh).

In case you haven't noticed, we weren't impressed by the defense, which would not have passed muster in any courtroom in the land. But our opinion doesn't matter, of course. Trump reportedly loved what he saw, while the Republican senators were able to extract enough to be able to hang their hats on. So, Team Trump did what they needed to do.

After the four hours set aside for questioning, during which nearly every question was deflected by Trump's lawyers, the Senate adjourned for the day. Today, each side will have 2 hours to summarize their case. Then, the senators will debate whether to call witnesses (no chance), and finally they will vote. By late afternoon today, barring the unexpected, The Donald will be cleared for a second time. And that may well be the last presidential impeachment ever, since...what's the point? (Z)

Saturday Q&A

Impeachment is on the brain, naturally.

Q: If 44 Senators believe the impeachment process is unconstitutional, they must stick to their guns and not be present when it comes time to vote. This would achieve a pair of outcomes: (1) they would be sticking to their convictions and no one can fault them for that, not even their constituents; (2) it would allow Donald Trump to be impeached by at least 2/3 of the remaining members. Justice would prevail and members on both sides would feel satisfied that they followed their consciences and did what is morally right. If the 50 Democrats and the 6 Republicans who voted to go ahead with the Impeachment vote in favor, then it would only take 16 Republican senators to be absent during the vote to be a 2/3 majority (56 of 84). Do you see any flaws in this scenario? R.W., Sea Cliff, NY

A: This is all correct, and is at least plausible. If Donald Trump is convicted, this is probably how it will happen.

That said, it is not very likely. First, it is implausible that Trump's base will be satisfied by the use of what is, in effect, a loophole. Whether a senator harmed the Dear Leader through action (voting to convict) or inaction (not showing up, and lowering the number of votes needed for a conviction), Trump and his allies in the right-wing media would be furious and would whip the base into a lather. The senators who fear the Trumpeters know this.

Second, if some or all of the 44 were planning to do this, they would not have sat through 2-3 days of hearings that clearly left them extremely bored. They would have jumped ship on the trial immediately following Tuesday's vote.

Q: If the Senate were to vote anonymously on Trump's impeachment trial, what do you think the possible vote would look like? S.C., Jonesville, MI

A: First, let us remind everyone of something we covered in previous mailbags: This is an entirely hypothetical scenario. By the terms of the Constitution, it takes just 20% of the members to force a secret vote to be made public. Further, even if that provision were not invoked, the senators who voted for acquittal would be all over Fox News, OAN, and Newsmax crowing about their loyalty to the president, which would make it easy to identify the apostates by process of elimination.

But if we imagine a world in which the balloting is secret, and is 100% guaranteed to remain secret for the next 50 years, then we would guess that it would be something like 80-20 for conviction. There are undoubtedly some true believers among the GOP senators (like, say, Mike Lee, UT, or Ron Johnson, WI). There are probably some additional number who fear a conviction will lead to further violence and division. However, the majority would like Trump purged from the party, either so the GOP can move past him, or in order to eliminate him as competition in 2024. Is there any question that Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), who is among the loudest pro-Trump voices in the Senate right now, would vote to convict if he knew for sure it would remain a secret?

Q: Why is the Senate voting on the constitutionality of the impeachment trial? I thought the Supreme Court decides what is and is not constitutional. R.T., Austin, TX

A: This is one of those areas where jurisdiction is indeed a little fuzzy. The Supreme Court has the power to weigh in on Constitutional issues, yes, but the Constitution also gives "sole authority" to the Senate when it comes to handling impeachments.

However, in 1992, Judge Walter Nixon was impeached and removed from his judicial office, and sued. In its decision in Nixon v. United States (1993), the Court declared that the question of whether or not the Senate had properly tried an impeachment was not justiciable, and was entirely up to the Senate to decide. Until someone files a case that challenges that precedent and then wins, the Senate gets to do whatever it wants.

Q: The Republicans have been saying for weeks that the Constitution doesn't say anything about a former president being impeached and so impeachment is unconstitutional. However, the Federalist Papers are often cited as a historical source to put constitutional provisions in context. Although they do not carry the legal weight of the Constitution or common law, they are still very important in determining the intent of the country's founders. What do the Federalist Papers say about impeaching former officials? K.E., Newport, RI

Q: Did the framers of the Constitution ever consider or anticipate the scenario that has unfolded in the last two impeachments? Namely that senators of the President's party either: (1) make a decision to acquit prior to the proceedings and ignore convincing evidence, or (2) work with the defense (conspire) to determine strategies for the proceedings? M.W.O., Fabius, NY

A: The two Federalist Papers to address impeachment are Federalist 65 and Federalist 66, both written by Alexander Hamilton. They address three major questions that the framers had wrestled with during their deliberations:

- Should impeachment exist?: This was a significant area of disagreement while the

Constitution was being debated. Some of the gentlemen there, most notably Gouverneur Morris, said impeachment

shouldn't be an option, as it might compel the president to kowtow to the legislature. Others said that

there has to be some way to remove a problematic chief executive. Ben Franklin dryly observed that impeachment

was a superior option to the one generally employed by the British against problematic kings, namely beheading.

Hamilton agrees that it is necessary to have impeachment available as a remedy.

- What is the basis for being impeached?: The authors of the Constitution used language that

they believed was clear, namely "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors." Hamilton thought that needed

some explanation, and so he elaborated on the meaning, namely "offences which proceed from the misconduct of men, or in

other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be

denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself." In other words,

Hamilton is saying that "high crimes and misdemeanors" means something different from "crimes and misdemeanors."

- Who should try an impeachment?: The framers toyed with several options, including the governors of the states and the federal judiciary before settling on the Senate. In Federalist 65 and 66, Hamilton addresses the alternatives, particularly the Supreme Court, and talks about why the Senate was the best choice—because they represent the people, and because of the high number of votes needed for conviction, removal by the Senate would have more credibility than removal by the Supreme Court. He does acknowledge that "there will always be the greatest danger, that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt." Very prescient.

So, in answer to M.W.O.'s question, the framers did indeed foresee this problem. They also didn't see an alternative that would allow them to avoid it.

Q: As it seems certain that Donald Trump won't be convicted (unless a bunch of GOP senators decide to skip the vote, so as to reduce the number needed for conviction), I have to wonder about the other way to ban Trump from further office, through the 14th amendment. Since insurrection and rebellion are codified as federal crimes, wouldn't a conviction on one of those ban him from office? And how likely might that be to happen? K.H., Ypsilanti, MI

A: There are a number of maneuvers that Congress might undertake in an effort to disqualify Trump under the terms of the 14th Amendment. They could adopt a motion of censure, for example, in which they declare him to have suborned insurrection. They could pass a law that entitles U.S. Attorneys to bring suit against Trump (or Ted Cruz, or Sen. Josh Hawley, R-MO), asking a court for a finding that they violated the 14th Amendment.

Alternatively, Congress could sit on its collective hands and let events take their course. An ambitious U.S. Attorney could decide not to wait for new legislation, and instead could go to court and ask for a finding under the terms of the Enforcement Act of 1870, which was originally passed in order to keep former Confederates from holding office. Or, a U.S. Attorney could try Trump criminally for sedition and for inciting insurrection. If the former president was convicted, that would surely be enough to trigger the 14th Amendment.

Given all the various means by which the 14th Amendment might plausibly be invoked, and given that Trump otherwise will suffer no consequences for his actions, we'd say the odds of at least one of these things coming to pass are pretty high—maybe 80%? If and when Trump is disqualified, then he would have to sue and hope that the Supreme Court overturns that finding.

Q: I'm staring at the marble (I'm assuming it's marble) wall behind the speakers at the

impeachment trial. It got me wondering, Jerry-Seinfeld-stand-up style: "What's the deal with the wall?"

Is it the same dais that was installed when the Capitol was built? Has it always been that color? Is it actually marble?

Where did the rock come from? Or is this a Resolute Desk situation where it's been around for a while, but not

forever?

N.M., Medford, OR

A: Up through 1859, the senators met in a room now known as the "Old Senate Chamber," at which point they decamped to the current Senate chamber. Thereafter, the old chamber was used for Supreme Court hearings (until 1935), then for informal Senate meetings and discussions (until 1976), and then was restored and turned into a museum.

The current Senate chamber, in its 1859 incarnation, was designed by Thomas U. Walter, who is better known for having added the dome to the Capitol. At that time, the chamber had features that were cutting-edge and fashionable, including skylights, steam-powered ceiling fans, and lots and lots of wrought iron. In 1949 and 1950, the chamber was redesigned to bring it up to date in terms of both technology and taste (well, the tastes of 1950). That meant electric lighting in place of the skylights, air conditioning in place of the ceiling fans, and marble in place of the wrought iron. The marble you see was installed then, and was quarried from Levanto on the Italian Riviera. It may appear to be black in color on TV, but according to LBJ biographer Robert Caro, it is actually "deep, dark red lushly veined with grays and greens."

Q: Could you please define "Overton Window"? G.H., Chicago, IL

A: The Overton Window describes the range of "acceptable" opinions on a subject.

Using minimum wage as an example, in 2015 a person could plausibly have been an advocate for a $7.25/hour minimum wage (i.e., the status quo) but pushing for anything less than $7.25 would have been seen as too restrictive, and so would have been broadly unacceptable and thus outside the Overton Window. Meanwhile, a person could plausibly have been an advocate for a $12/hour minimum wage (i.e., Hillary Clinton's proposal), but pushing for anything more would have been seen as too generous, and so would have been broadly unacceptable and also outside the Overton Window. Put briefly, the Overton Window for the minimum wage discussion was $7.25/hour to $12/hour.

Of course, in 2016, Bernie Sanders' presidential campaign caught fire, in substantial part due to his support for a $15/hour minimum wage. Eventually, he dragged most other Democrats to his position, including Clinton. And so, the Overton Window for the minimum wage discussion these days is $7.25/hour to $15/hour. Most Americans favor a number that is somewhere in that range, while anything outside that range would be pretty fringy and would not have much support.

Q: Can you please explain why the House is fixed at 435 members? It seems like such an arbitrary number. Where did that number originate, and why does it never change? P.M., Currituck, NC

A: From 1792 through 1911, Congress passed a series of apportionment acts that slowly increased the size of the House as the nation's population grew, using a variety of mathematical formulas. The last of those apportionment acts, the one passed in 1911, set the number of seats at 435.

In 1920, the Republicans gained control of the House, Senate, and White House. And they realized that the customary reapportionment that should have taken place in 1921, following the completion of the 1920 census, would be very painful for the GOP since the lion's share of the population growth from 1910-20 had been among Democratic constituencies. So, the Republicans ignored the census and left the apportionment as it was. We know it's hard to imagine the Republicans brazenly ignoring the plain text of the Constitution to maintain their hold on power, but it happened!

Finally, in 1929, (correctly) sensing that their total control of the federal government was nearing its end, the GOP-controlled Congress passed the Reapportionment Act of 1929, which made the 1911 seat total permanent. The 1929 legislation has never been revisited because:

- It's now traditional, and Americans like tradition

- It tends to favor the minority party, which would push back against any change

- House members don't want their individual slice of power to become smaller

- It would be hard to find enough space for another 200 or 300 or 500 members, both in terms of seating in the House chamber and in terms of office space

None of these things is impossible to overcome, but don't hold your breath waiting for a change.

Q: I have been trying to find out on what date Nina Turner's election will be held. I have searched high and low and I can find nothing. Even on her website. What gives? C.B., Columbus, OH

A: Nina Turner, for those who do not recognize the name, is the leading progressive challenger for the House seat that will be vacated by Marcia Fudge if and when she is confirmed as Joe Biden's Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

Because Fudge has not yet vacated her seat, Gov. Mike DeWine (R-OH) cannot set a date for the special election. That said, the state already has set aside May 4 for any primaries that might be needed, and Aug. 3 for any special election that may be needed, so those dates are likely unless it takes a long time to confirm Fudge.

Q: What happens if Sen. Pat Leahy (D-VT) dies? Doesn't Vermont have a GOP governor? J.F., Atlanta, GA

A: Yes, Gov. Phil Scott (R-VT) is indeed a member of the GOP. However, by the terms of Vermont law, he would be required to call a special election to fill a Senate seat no more than 6 months after it became vacant. And when there was talk of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) possibly resigning for a cabinet seat, Scott committed to choosing a Democratic-leaning independent. Presumably he would do the same if Leahy's seat came open.

Q: If there is any doubt about being able to push through a $15 minimum wage under the budget reconciliation process, why not include it as a tax? For example, "employers with more than X employees receiving less than $15/hr in wages will be charged a public benefits tax of $15,000 per year per employee." Clearly, new taxes are allowed under the budget reconciliation rules. I can't be the first to think of this—since it seems like the more bulletproof approach, why isn't it being used? M.H., Boston, MA

A: The bigger issue, at this point, appears to be getting all 50 Democrats on board with $15/hour, rather than finding a way to keep Senate Parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough happy. If all 50 Democrats agree to $15, then the approach you propose would certainly work. However, the recent CBO report on a $15/hour minimum wage, which predicts various and substantial budget impacts, is probably enough to satisfy her as well, rendering further maneuvering unnecessary.

Q: While perusing an authoritative encyclopedia on the more transformational Presidents of the United States, I came to the conclusion that although Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced sweeping changes to the way American government works and was significantly criticized for this, his electoral opponents for reelection—Alf Landon, Wendell Willkie and Thomas Dewey—seem to have been all rather careful and lukewarm in their opposition, although they represented a well-established party that had been ousted after decades of dominance. From today's point of view, one would expect fire-breathing Republicanism rather than His Excellency's Most Loyal Opposition. Did FDR charm even his nominal opponents into submission? F.R., Berlin, Germany

A: Not exactly. There were, we would say, three dynamics going on here. First, in the middle of a national crisis like the Great Depression or World War II, it is somewhat poor form for a challenger to get out his acid tongue. Second, there was plenty of mud slung in those campaigns, but mudslinging was generally not seen as apropos for the fellow at the top of the ticket in that era, and instead was left to those lower on the totem pole. Third, and probably most importantly, the Republicans went with the sort of milquetoast "the business of America is business" candidates that had worked so well for them for a long time (with Theodore Roosevelt being the main exception between 1876 and 1932). It took the GOP a while to figure out they needed to find a different sort of candidate if they wanted to beat the FDR coalition.

Q: Lots of speeches today quote earlier momentous speeches, as if by using the excellent prose of another era, the current speech can usurp some of the earlier speech's gravitas. Do any of those earlier speeches, like those in your recent top 10 list, quote even earlier speeches? If so, what are some eloquent quotes from those earlier speeches, and does current society remember any of those quotes in their own right? D.C., Brentwood, CA

A: Using direct quotations from past historical figures is largely a matter of personal style. Ronald Reagan, for example, did it a lot, often peppering his speeches with lines from Thomas Jefferson or Alexander Hamilton or George Washington. Barack Obama, on the other hand, almost never did it. Nor do most top-flight public speakers, since it's kinda cliché.

It is also somewhat common to take an earlier quotation and update it to be tighter and more modern. Although the speech just missed our top 10, surely the most famous example of this is "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country." There, JFK (or, more likely, speechwriter Ted Sorenson) appears to have been leaning on an 1884 address by Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who said: "We pause to become conscious of our national life and to rejoice in it, to recall what our country has done for us, and to ask ourselves what we can do for our country in return." It's possible that JFK/Sorenson did not borrow from Holmes directly, but instead got the idea through an intermediary source who had also borrowed from Holmes, possibly Kahlil Gibran, Warren Harding, or FDR, who all said similar sorts of things at various times after 1884 and before 1961.

Far and away the most common thing to do, however, is to reference an earlier quote/work without directly lifting the exact words. Pretty much every 19th century president dropped references to scripture into their speeches, with Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address a particularly notable example (it makes clear allusions to the Book of Genesis, the Sermon on the Mount, and the Book of Matthew). It was also common to make reference to the works of classical Greek and Roman orators, poets, and authors. To use Lincoln as an example again, the Gettysburg Address is essentially an American version of Pericles' Funeral Oration.

Q: Using the definition of war crime from Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, who's the last president (not counting Joe Biden) that has a compelling case they didn't commit any war crimes during their tenure? J.M., Nova Scotia, Canada

A: We will begin by noting that the case that Donald Trump or Barack Obama or Bill Clinton committed "war crimes" is based on three basic assertions: (1) civilians were killed (2) indiscriminately (3) outside the boundaries of a duly established combat zone. But the most recent Geneva Convention was adopted in 1949, and the nature of war has changed a fair bit in the subsequent 72 years. It is not at all clear that something like drone strikes undertaken to suppress terrorist activity should be deemed war crimes, since the matter hasn't been adjudicated.

Put another way, the case against some presidents (Richard Nixon, George W. Bush, LBJ) is considerably stronger than the case against others (Trump, Obama, Clinton). That said, the last two presidents who seem unambiguously innocent to us are Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford, who were both strongly non-interventionist. However, even they have been accused of "war crimes" by some on the left, not because of any actions they took, but because of their failure to withdraw support for genocidal regimes, like the one in Indonesia that was making war against the people of East Timor in the 1970s.

If a president can be guilty of war crimes not only through action, but also through inaction, then you would have to go way back to find a president whose hands are completely clean. Probably to one of the 19th century presidents, like Benjamin Harrison. Of course, those presidents oversaw a harsh policy toward the Native Americans, which could make them guilty of war crimes, too.

We guess the point is this: "War crimes" has been deployed so regularly and so casually, and its formal definition is so out of date, that the term isn't all that meaningful. Probably best to judge each president individually.

Q: What portrait of Barack Obama will hang in the White House? Will it be the Kehinde Wiley that is currently in the National Portrait Gallery? And does the same go for Michelle Obama's portrait; will hers be the Amy Sherald portrait? D.L., East Lansing MI

A: The Obama portraits at the National Portrait Gallery are the property of that gallery, and so will remain there. White House portraits tend to be more formal, and are the result of a partnership between the former president/first lady, an artist (or artists) they approve, and the White House Historical Association (WHHA). Since it was clear that Donald Trump had no intention of holding an unveiling ceremony, the WHHA did not start the collaboration process, and so there are no portraits (or artists) as yet. Now that Joe Biden is in office, the WHHA will surely get the ball rolling. Well, once the pandemic is over, that is.

Q: What are the 10 best laws passed by Congress? F.S., Cologne, Germany

A: Here's our list:

- Northwest Ordinance (1787): The guide for the addition of another 37 states to the Union

- Pacific Railroad Act of 1862: Connected the East and the West, inaugurated an era of prosperity

- Homestead Act (1862): Millions of families got their grubstake thanks to this bill (albeit at the expense of the natives, in many cases)

- Wagner Act (1935): Legitimized labor unions and gave them important legal protections

- Medicare and Medicaid acts (1965): The yin to Social Security's yang, further committing the government to the well-being of its elderly (and poor) citizens

- Federal Reserve Act (1913): Gave the government an important and necessary tool for managing the economy

- Civil Rights Act of 1866: Extended citizenship to all people born in the U.S., laid the groundwork for the 14th and 15th Amendments

- GI Bill of Rights (1944): Lifted millions of veterans from the working class to the middle class by letting them get a home, an education, or both

- Civil Rights Act of 1964: It didn't completely eliminate racism, but it was a good start

- Social Security Act (1935): Committed the federal government to the care of its elderly citizens

Note that we're using the common names here, and not the formal ones (for example, the GI Bill of Rights is properly called the Serviceman's Readjustment Act of 1944). As always, let us know if you think we missed one.

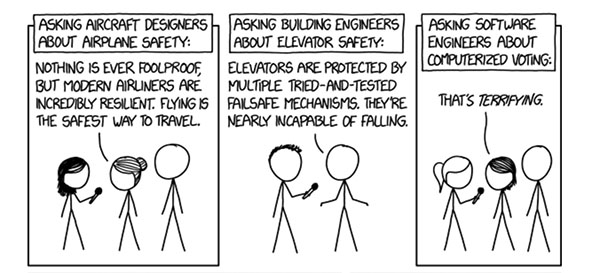

Q: You stated that internet voting "is not safe and cannot be made safe." I tend to agree with you, but could you expand on this a bit, given that many people bank entirely online, have their 401(k)s online, and so on? R.C., Louisville, CO

A: Voting has to be more secure than anything else, including banking, taxes, identity, and applying for a passport. The stakes are greater than for anything else. Internet voting is pushing the envelope in many ways. Iowa couldn't even count 175,000 caucus votes. That's chicken (or maybe hog) feed. The risk is so great and the benefit over absentee voting is so small, that it is not worth taking the risk.

Vladimir Putin is not prepared to hire the smartest people in Russia and spend a billion rubles to hack your bank account. He is most definitely prepared to do that to pick the president (and Congress) of his choosing. Also, the counties, states, and federal government simply do not have the expertise to run a digital election. They would have to hire an outside company to do it. Can this company be trusted when the CEO knows that if candidate A wins, corporate taxes go up but if candidate B wins, corporate taxes go down?

Internet banking really isn't safe. Banks are hacked all the time. They just pay off the victims in return for their signing an NDA to keep quiet about it. If hacking raises their costs by, say, 2%, the banks just write it off as a (tax-deductible) cost of doing business. Changing the vote by 2% in three or four states would change the election result. If you think that big financial companies know what they are doing, remember that in 2019 Capital One Bank was hacked and 100 million people were compromised. A couple of years earlier, Equifax was hacked and critical financial information on 150 million people was stolen. This happens all the time, but only the really big ones make the news. If you want a list of major hacks, try this one. There are many banks and giant corporations on the list. Those who say "I have never been hacked so I don't believe hacking happens" are basically saying the equivalent of: "I have never had a car accident so I don't believe car accidents happen."

The federal government isn't even capable of protecting its own secret and military systems from hacking. Do you really think that county officials, many of whom couldn't tell a CPU from an RJ45 and who don't want the big bad government telling them how to run their elections, could hold the SVR or GRU at bay?

There are millions of people who don't have a computer, iPad, smartphone, Internet access, or an e-mail account. Can these people vote? These people are predominantly poor and/or minority. We suspect that one of the parties might see this as a feature, not a bug, and be all for Internet voting. We won't tell you which party, though.

And how would you identify voters digitally? Send everyone an envelope with a login name and password? The government envelopes would all look alike. Could postal workers or letter carriers be bribed to steal them in bulk to let four campaign operatives somewhere in a secure basement vote for 100 voters? That trick doesn't work for absentee ballots because a signature is needed. Sending a PIN code in a separate letter doesn't really help because those letters could be captured too, and many people would be confused by the process. Some banks use two-factor authentication and send a code to your phone to verify your identify when logging in but many poor people don't have a cell phone.

Scams would abound. Scammers would call people and say: "I'm from the county. There was an error in the password we sent you. Tell me your password to verify your identity and I'll give you your new password right now." If you believe no one would fall for this, we have a lovely bridge in Brooklyn that you can have for only $1,000 in bitcoin.

There is no paper trail to audit in the case of a close election with online voting. If the computer says Mary Jones won, then her opponent, Ellen Smith, is out of luck. The coronavirus isn't the only one in town. Many computers are infected with viruses, too. That's why there is a whole industry selling antivirus software. Viruses in infected computers could change a vote for Smith to Jones before encrypting and transmitting it and no one would be any the wiser. With Internet voting, there would soon be a whole industry creating and deploying vote-changing software—for example, disguised as apps to allow people to view and submit short videos.

It would also be hard to maintain a secret ballot. When a voter logged in, the system would know who they are. It would have to in order to make sure only registered voters could vote and do that only once. The message to the county with the vote could be encrypted to protect it from being modified in transit, but the county would still have to know who cast the vote. It would be hard to prevent determined and knowledgeable county workers from seeing who voted for whom and potentially selling that information. E-banking does not have a secrecy requirement. In fact, banks go to a lot of trouble to determine precisely who is trying to log in.

There has been a lot of academic research on digital voting, but all of it depends on using higher mathematics in very complex ways. More than 99.9% of the voters are incapable of ever understanding this and simply would not trust the election process. Even with paper ballots that are auditable and in some cases (Georgia) have been hand recounted multiple times, half the country doesn't believe the result. Can you imagine what it would be like if Anthony Fauci were replaced by an MIT computer science professor trying to explain a system that half of his MIT colleagues don't understand?

If you want the take of a Stanford computer scientist who is an expert on voting procedures, check this out. You heard somewhere that a thing called "blockchain" will solve everything? Experts at Harvard and MIT think that will only make things worse.

And if this is all too complicated, how about a cartoon from xkcd that summarizes it?

Q: I've wondered often about how you guys seem to know a lot about an awful lot of stuff—from history to the workings of Congress and the judiciary, for example. When you gave your opinion about the difference between AOC and MTG and got into the use of plosive letters (thanks for the link), I knew I had to ask the question: How are you able to be so knowledgeable about so much? Do you have a staff that works with you to do some research, or is it all on you two? And if you have staff, are they strictly volunteer? R.P. in Northfield, IL

A: We don't generally like to pat ourselves on the backs, but we get variants of this question almost every week, so we decided to answer it. We have assistance with the technical aspects of the site, with inputting polls, and with copy editing. However, we do not have a research staff, and everything you read (except guest posts) was written and researched by one or both of us. Here are some potentially useful explanations for our breadth of knowledge:

- Although academia tends to encourage narrow but deep research, we both followed more of a broad path. Neither of us

studies the things that were traditionally associated with our Ph.D. degrees when we started grad school; one of us is

an astrophysicist who ended up doing computer science, and the other is a historian who does memory studies.

- Consistent with the previous answer, our specialties tend to be very complementary. One of us does the science and

math, one of us does the history and civics. To take a specific example, one of us wrote the answer about the 10 best

laws from Congress, and the other wrote the answer about Internet voting. You'll have to guess who did which one,

though.

- You don't get a Ph.D. without getting very good at research, and so we both know how to find out the things that we

don't already know. Also, we have many colleagues we can consult to double-check things we're not 100% sure about.

- We pick the questions we answer, and the subjects we write about. So, we do have some ability to steer things in directions we know.

If you wish to contact us, please use one of these addresses. For the first two, please include your initials and city.

- questions@electoral-vote.com For questions about politics, civics, history, etc. to be answered on a Saturday

- comments@electoral-vote.com For "letters to the editor" for possible publication on a Sunday

- corrections@electoral-vote.com To tell us about typos or factual errors we should fix

- items@electoral-vote.com For general suggestions, ideas, etc.

To download a poster about the site to hang up, please click here.

Email a link to a friend or share:

---The Votemaster and Zenger

Feb12 What's Next for the Republicans?

Feb12 It Will Be a Taxing Year for Trump

Feb12 Former Republican Officials Consider Forming Center-Right Party

Feb12 Biden Administration Grapples with COVID-19

Feb12 Biden Administration Also Grapples with Clemency

Feb12 Diplomatic Unity?

Feb11 The Impeachment of Donald J. Trump, A Tragedy in Three Acts

Feb11 Atlanta DA Has Opened a Criminal Investigation of Trump's Call to Raffensperger

Feb11 Senate Judiciary Committee Will Hold a Hearing on Merrick Garland Feb. 22-23

Feb11 Poll: Huge Majority Wants COVID-19 Relief Bill to Pass

Feb11 Biden Can Now Find Out What Trump Said to Putin

Feb11 Republicans See Themselves as the Party of the Working Class

Feb11 How the Republicans Plan to Win Back the House

Feb11 Nearly 140,000 Voters Left the Republican Party in January

Feb11 "Trump in Heels" Frustrates Virginia Republicans

Feb11 Politics Makes for Strange Bedfellows

Feb10 There's a Right Way and a Wrong Way...

Feb10 Lessons Learned

Feb10 Good News, Bad News for Fans of a $15/hour Minimum Wage

Feb10 Biden's Getting His Cabinet, Slowly but Surely

Feb10 Democrats Focus on the Suburbs

Feb10 Presidents' Best Friends

Feb10 About Those 1980s Movies...

Feb09 Deja Vu All Over Again

Feb09 Parscale Suggests Trump Run as Martyr in 2024

Feb09 Raffensperger's Office Launches Investigation into Trump Phone Call

Feb09 No DeJoy in Mudville (at Least, Not Yet)

Feb09 Red-colored Sharks Are Circling Newsom

Feb09 Fetterman Throws His (Sizable) Hat into the Ring

Feb09 Rep. Ron Wright Succumbs to COVID-19

Feb08 Key Questions about Trump's Trial

Feb08 The Trial Could Be a Public Relations Disaster for the Republicans

Feb08 No More Dog Whistles

Feb08 Biden Doesn't Think the $15/hr Minimum Wage Will Be Allowed in the COVID Bill

Feb08 Trump Won't Get Intelligence Briefings

Feb08 Fox Is Worried

Feb08 "You Probably Haven't Heard of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson"

Feb08 Report: Shelby Won't Run in 2022

Feb08 Boebert Has Three Democratic Opponents Already

Feb08 Judge Says Tenney Won

Feb08 What Is the Defense Production Act?

Feb07 Sunday Mailbag

Feb06 Saturday Q&A

Feb05 America First Couldn't Last

Feb05 Greene's New Deal

Feb05 Trump Refuses to Testify

Feb05 The Day AFTRA

Feb05 Double Trouble for Fox News

Feb05 Pence Makes His Move