Saturday Q&A

We were pretty sure there would be a lot of questions about critical race theory (CRT) and related issues. We were right.

Q: You listed six basic tenets of CRT. For me, and I imagine most E-V.com readers, tenets 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 are so obvious that they could hardly be the basis for a distinct analytic approach to history, the legal system, social sciences, etc. The essence has to lie in tenet #3:

Owing to what CRT scholars call "interest convergence" or "material determinism," legal advances (or setbacks) for people of color tend to serve the interests of dominant white groups. Thus, the racial hierarchy that characterizes American society may be unaffected or even reinforced by ostensible improvements in the legal status of oppressed or exploited people.

Unfortunately, it's a bit of a head-scratcher for me. Unless I'm misunderstanding it, it's saying that decisions like Brown v. Board (1954), legislation like the Voting Rights Act (1965), and policies like affirmative action (in, say, hiring) reinforce structural racism. Now, I can understand how, if one takes a certain broad-minded view, the interests of the capitalist ruling class are served by reducing racial conflict and there are certainly elements in the ruling class that see things this way. But that doesn't mean that Brown, voting rights, and affirmative action hurt Black people. Does it? Can you explain this a bit more? And give an example or two that really gets concrete? D.A., Brooklyn, NY

A: Keep in mind that the folks who developed CRT were (and are) engaging with the dominant narrative of the Civil Rights Movement, namely that Black people demanded justice, white people were persuaded by their determination and righteousness, important laws were passed, and great progress was made.

CRT does not reject any of these notions in their entirety, it merely tries to complicate them, and to encourage people to think critically about them. Most CRT scholars would not say that white people never acted magnanimously and out of a desire to do right by people of color; merely that there were benefits for some (or many) white people in nearly every step toward greater equality, and those benefits may have been a significant part of the motivations of the (white) people in power. For example, did Lyndon B. Johnson support the Voting Rights Act because he believed it was the right thing to do, consequences be damned? Or did he support it because he knew that conservative, white Southerners were slipping out of the grasp of the Democratic Party, and he wanted to replace them with some other constituency? Or maybe both?

Similarly, CRT does not posit that all steps toward greater equality hurt Black people, merely that some did, and that one should not assume that all "progress" is actually progress. Or, even if it is progress, it may not be unambiguously progress. For example, Brown decreed that segregated schools were not permitted, but in so doing made possible a situation where "integrated" schools had some overwhelming percentage of white students (90% or more) and some small minority of, well, minority students. And depending on the place and time, those minority students were effectively stuck on an island, treated as outsiders or outcasts by most of their fellow students (and some of their teachers), while also being taught versions of history, literature, etc. that had no room for their experiences. Were Black people, as a whole, better off due to integration? Certainly, particularly in the long term. But were those students on an island, like, say, the Little Rock Nine, better off? Maybe not.

Q: Regarding the second tenet of CRT, namely "Racism in the United States is normal, not aberrational," would understanding that racism or similar bigotry has been the norm most of the time in most places make it less controversial? Of course, that may not sit well with "American exceptionalism", since the U.S. is not all that exceptional in this aspect. T.L., San Francisco, CA

A: We don't think that there is any amount of context, or any carefully chosen verbiage, that would be satisfactory to those who rebel against racism as a part of the narrative, while also passing muster with those who insist that racism must be a part of the story. Particularly since, as you note, racism significantly complicates the notion of American exceptionalism. In (Z)'s experience, many folks who embrace an exceptionalist view prefer to ignore race/racism entirely, or else to treat it as an aberrational attitude held by a long-deceased minority of citizens.

Q: I grew up in California, but have never heard of CRT until a few months ago. If this has been around since the 1960s, why haven't I heard anything about it until now (even in my many Poli Sci classes)? J.H., El Segundo, CA

A: The reason you didn't hear about it in class is because it is largely not appropriate for undergraduate courses. Broad, theoretical frameworks are really hard to communicate to students, particularly if those frameworks are still evolving. It is true that if a particular theory or interpretation has been profoundly impactful, then you may have to engage with it in an undergraduate course. Put another way, someone with a general education should probably have some idea what Communism is, and what Darwinism is, and what Transcendentalism is. But CRT does not come close to clearing that bar in terms of influence, and is the sort of thing that you learn in graduate or professional school. It's possible that some course content in an undergraduate course might be influenced by CRT, but it would be very unusual to actually get into the underlying framework.

The reason you are hearing about CRT now is because it was an influence on the 1619 Project. Many right-wing types immediately glommed onto the Project in general, and CRT in particular, as culture-wars wedge issues.

Q: What is your view on the validity of the 1619 Project with regard to its historic credibility and suitability for use in American classrooms? M.O., Arlington, VA

A: It's helpful, if used properly. Broadly speaking, there is much value in helping students to understand that history is not some immutable set of truths, like the laws of thermodynamics or the periodic table are, and that the same historical personages, events, and eras can be understood in radically different ways, depending on who is doing the understanding. Since students aren't always great at picking up on subtleties, these sorts of exercises work best with interpretations that are pretty far apart. For example, a discussion of the 1619 Project essay "The Barbaric History of Sugar in America," by Khalil Gibran Muhammad, and a selection from American Negro Slavery, by Ulrich B. Phillips (main thesis: white people did Black people a favor by enslaving them), could be instructive.

It is also not so easy to get students these days to do the reading for a course, even if they will lose points by not doing it. So, selecting one of the more provocative and intriguing essays from the Project could also be a useful teaching strategy. For example, "What the Reactionary Politics of 2019 Owe to the Politics of Slavery," essay by Jamelle Bouie could pique many students' interest, because they like to understand how the past and present connect, and because Bouie is a very good writer. Similarly, "Why Is Everyone Always Stealing Black Music?" is the sort of thing that students might be drawn to.

Using the 1619 Project as the sole curriculum for a history course would not be a great choice, given some of the flaws as well as the lack of balancing viewpoints. However, it's not really designed to be a standalone curriculum. It's meant to be used as a supplement.

Q: Thanks for the item on CRT. I agree that the antagonists do not understand what they hate. How does the current conservative blowback compare to the blowback around ten years ago against Common Core? I never understood conservative's problems with that one either. Are there common threads between CRT and Common Core that got them stirred up? R.T., Arlington, TX

A: There are a few longstanding undercurrents in American thought that are particularly common among conservatives, though they can be found among liberals as well:

- Education is for elitist snobs

- Schools do not teach, they indoctrinate

- The government, or some part of it, is up to no good, and may be conspiring against its citizens

These sentiments mean that many Americans have distrust of schools (one major reason there is a lot of homeschooling in the U.S.). When some entity, whether the government or—apparently—The New York Times actually tries to promulgate a specific curriculum, or even a set of suggestions about the curriculum, that really sets off alarm bells in the minds of some citizens. The National Standards for United States History triggered the same response, back in the 1990s.

So, CRT and Common Core are similar in that way. They are otherwise pretty different, in that Common Core was more comprehensive, largely rooted in fact rather than interpretation, was crafted based on substantial public feedback, and had support from both Republican and Democratic officeholders. There are valid criticisms to be made of Common Core, just as there are valid criticisms to be made of CRT. However, the fact that the most outspoken opponents rarely seem to be able to articulate those criticisms, and that the reaction to CRT/Common Core was so similar despite their actual content/function being so different, suggests that the problem is the very existence of a plan for what should be taught, and not the actual content of the plan.

Q: We now have Juneteenth as a national holiday in 2021 (Yes, as I cry with happiness). I am surprised there was not much debate about it, as there was with MLK, Jr.'s birthday. How many federal holidays are possible? Will making Election Day a holiday be more difficult now? Or, perhaps because of the pandemic, working from home has many synergies, and nowadays we can afford more federal holidays? M.G., Indianapolis, IN

A: It is indeed a surprise that Juneteenth came together so quickly, given how controversial the MLK, Jr. holiday was. Heck, we follow politics very closely, and had no idea it was even on the docket until just days before it passed. You're probably right that the pandemic influenced people's thinking about days off, though we know no way to prove that.

Given how rapidly members of both parties (excepting 14 House Republicans) lined up behind Juneteenth, we have no idea exactly how much potential there is for additional future holidays in the near future. However, we can tell you two things. The first is that federal holidays are only binding on the federal government itself. States often choose to follow suit, and so too do private businesses, but they do not have to. For example, Columbus Day (or, in some states, Indigenous Peoples' Day) remains an official federal holiday, but few businesses honor it.

One thing the federal government could do if it were so inclined, is put a clause in every federal contract stating that one of the conditions of the contract is that the contractor give all but essential employees a paid holiday on Juneteenth, Election Day, Groundhog Day, or whatever. It could also require the contractor to put the same conditions on its subcontractors, and their subcontractors, and so on ad infinitum. That would greatly increase the number of people getting a paid day off.

The second thing we can tell you is that the United States is the only industrialized nation with no legally mandated paid leave. The average employee in the U.S. gets about 28 days' paid leave per year (holidays, vacations, sick days), but that is entirely voluntary on the part of the employer. And that puts the average American worker about 5-10 days per year behind most European nations. So clearly, more holidays are plausible.

Q: This might be a technical in the weeds kind of question, but why is Juneteenth called Juneteenth? You have to admit it is an unusual designation. I always assumed that it was called that because the actual date that the news got to Galveston was unknown, but apparently I assumed incorrectly. D.E., Lancaster, PA

A: Nobody knows for sure, and it's likely that we'll never know for sure. That said, here are a few things that we can say with confidence:

- When it comes to Black culture and, in particular, Black linguistic patterns, there is very, very little evidence

left from the 19th century. Black folks were much less likely than white folks to have things like newspapers and books

produced by members of their community and, even if they did, it was less likely that those things would be saved. So,

tracing the origin of the term in real time is not possible, although it does not seem to have emerged immediately

(i.e., in 1865).

- The term first began to appear in white people's newspapers in the 1890s.

- That said, "Juneteenth" does not appear to have achieved wide circulation until the 1930s and 1940s.

- There is clear linguistic-evolutionary pressure to turn the date into a portmanteau. As we've noted before, such as in our discussion of "AOC" vs "MTG," some combinations of syllables are much easier to utter than others. "Juneteenth" offers a clear savings of time and energy over "June Nineteenth," because of that hard 'n.'

It could be that the evolutionary pressure is the end of the story. But if there's more to it than that, well, we can't tell you for sure what that "more" would be. We can, however, give you a few theories:

- Mockery: One of the earliest known references to Juneteenth comes from a Southern

newspaper in which the event is referred to, derisively, as a "Juneteenth silibrastion." It could be that the term

first emerged as mockery of Black dialects, but then was appropriated in the same way that LGBTQ+ folks have

appropriated some of the slurs directed at their community.

- Black Pride: Alternatively, "Juneteenth" began to catch on around the same time

as the Harlem Renaissance, when many Black Americans were searching for and celebrating distinctive aspects of

their culture. They might have gravitated toward the use of a distinctive phrase so as to set the day apart

and to give it a name inspired by the Black community.

- Headlines: There are many abbreviations, acronyms, portmanteaus, etc. that were

adopted primarily to fit the needs of late-19th and early-20th century printing presses, with space at a premium

on newspaper pages and leaflets and the like. Think "TR" for "Theodore Roosevelt" or "Axis" for "Germany, Italy,

and Japan." It could be that, in print, it was not clear that "June 19th" was referring to a holiday, while

"June nineteenth" was a bit on the long side.

- It's Louisiana's Fault: Because of the presence of the French language, and several languages brought over from Caribbean nations, some communities in Louisiana pronounce words in a very distinctive way, basically swallowing certain consonants. Most notably, some Louisianans don't generally pronounce the letter "r" (which makes them "non-rhotic," to use the linguist's term), but some also swallow or under-pronounce "n." Perhaps, as the holiday made its way across the South, "Juneteenth" was the "Cajun" pronunciation, and it somehow caught on.

Again, these are just guesses.

Q: Happy Juneteenth! It was reported that in the Senate the bill to make Juneteenth a national holiday was passed by unanimous consent. How does unanimous consent work in terms of the process? It has been noted that the Senate rarely has all senators on the floor, and usually just one speaking to an empty chamber (I've seen it myself from the gallery). Are all the other senators generally hanging out in their offices and have a certain amount of time to object to the UC petition? Or will senators know that the request for UC is coming up by way of a floor schedule, or something like that, and therefore will be ready in chamber to object? And how much time, in hours, is saved by UC being accepted instead of using the normal process? M.U. Seattle, WA

A: Like so many Senate procedures, UC did not exist at the beginning of the republic. It was first used in the antebellum era, was codified in Senate rules in the 1930s, and became a truly useful parliamentary maneuver in the hands of a fellow named Lyndon B. Johnson when he was Senate Majority Leader.

In any event, UC is often used for very basic functional purposes, like adjourning without a formal vote to adjourn. However, when it is used to pass legislation, there is almost always some amount of groundwork laid by Senate leadership, as they check in with members to confirm their support, and to negotiate any conditions that need to be established. For example, there will often be an agreement that a senator's remarks on a piece of legislation will be directly entered into the Congressional Record, without having to be read on the floor of the Senate, if the senator agrees to UC.

As a general rule, it is made clear when the UC request will be made, and that request usually takes place when most or all of the senators are going to be on the floor anyhow. Since the Senate makes (and enforces) its own rules, literally any step (or all steps) in the legislative process can be skipped if everyone agrees. While it is not likely to happen, a person could walk into the Senate chamber with a bill that nobody there had ever seen before, and it could be passed 30 seconds later by UC. That means that UC can theoretically save a limitless amount of time, since it can not only skip over committee hearings, floor debate, etc., but also a filibuster.

Q: If you were drafting your Fantasy Senate Team, which of the following do you think would be the

least-bad final pick—picking Joe Manchin as the 50th Democrat, or picking Rand Paul as the 50th Republican?

Assume that your team already controls the House and the tie-breaking vice president. Which Senator would be a bigger

hindrance to your agenda?

D.T., San Jose, CA

A: This is easy; you should choose Manchin. He votes with the Democrats 70% of the time, and those occasions where he does not are largely predictable. It remains unclear if he's really and truly willing to hold the line against his Party's priorities, like voting rights and changing the filibuster, but in any case, he will certainly respond to traditional types of influence, including reason, arm-twisting, and pork.

Paul, by contrast, is a loose cannon who is convinced that (1) he's smarter than everyone else, and (2) he's on a crusade to accomplish...something. Even his own party is often unable to understand where he's coming from, and he can be impossible to "whip" when it becomes necessary. Plus, he's prone to grandstanding and cheap, attention-getting tricks, and Manchin is not.

Q: If Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) retires from his seat in the House, does Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) have the option to make a temporary appointment to fill the position, or does it sit empty until a new election or special election takes place? I ask because of my nightmare scenario: Gaetz retires, DeSantis appoints Donald Trump to the House seat, House Republicans turn on Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and make Trump the minority leader until they win back the majority in the House. Trump then becomes the House Majority Leader/Speaker of the House, where he runs the show from his D.C. hotel, thus creating a "shadow presidency" and able to lob political grenades in any direction he wants, just like the old days. R.P., San Diego, CA

A: Keep in mind that Trump need not be a member of the House to be named Speaker. And since there is no constitutional basis for the leadership positions, he need not be a member to be named minority leader, either. If Republicans were willing to do this, they could do it anytime. You will notice that they have not, in fact, done this, nor given any indication they plan to.

As to Gaetz' seat, Article I, Sec. 2 of the Constitution specifies that "When vacancies happen in the Representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such Vacancies." In other words, it is not legal to appoint someone to a House seat, even temporarily. Senators, yes, but not representatives. The logic here, in case you were wondering, is that a governor represents the same constituency a senator does (i.e., the whole state) but not the same constituency a representative does.

Q: About this "Trump for Speaker" idea: Assuming he is elected Speaker of the House by a new Republican majority, that makes him second in the presidential line of succession, right? Or is there an exception for someone who is not also a member of Congress? J.C., Eugene, OR

A: He would indeed be second in the line of succession. There are no exceptions, other than being ineligible to the presidency (for example, a Speaker who was not native-born would be skipped in the line of succession).

Q: Paranoia strikes deep, and currently the support for Donald Trump as Speaker of the House comes from a small group of Trump fanatics. That said, it only takes a small group of fanatics to stage an insurrection or attempt a coup. Given that the Speaker of the House is second in line for the presidency, how much fanaticism do you think it would take to "remove" the president and vice-president and elevate Speaker of the House Trump to the highest office in the land? If the Democrats lose the House in 2022, Trump can be appointed Speaker of the House and simply wait on the lunatic fringe to do their part. H.J., Victoria, BC, Canada

A: Hmmmm...should we be wary of giving too much intel to someone from the Great White North?

If you are talking about impeachment, that is an impossibility. Even if the Democrats lose every single seat that is up in 2022, they would still control 36 seats in the Senate, and would be able to quash an impeachment.

If you are talking about assassination, that is a near-impossibility. It is true that on the night Abraham Lincoln was killed, the conspirators also tried to kill VP Andrew Johnson, and might even have succeeded, if George Atzerodt hadn't gotten drunk. But that was more than 150 years ago. It is also true that John F. Kennedy (presciently) observed that if someone wanted to trade his life for the president's, he could. But that was more than 50 years ago. These days, the Secret Service is really, really good at what they do. Getting to either Joe Biden or Kamala Harris would take a near-miracle for someone with assassination on his mind. Getting to both of them at the same time would take multiple miracles, since if the President was killed, the USSS would amp up security on the VP (now President) so much that even oxygen would have trouble reaching her.

This is not to say that the MAGA fanatics won't persuade themselves this is possible. After all, these are folks who also thought they could overthrow the government, and think that Trump can be "reinstated." So, there are no limits to their ignorance (or is it delusions?). But it's not happening.

Q: What do you think of Nancy Pelosi's claim that what the Department of Justice did under Donald Trump, with regards to subpoenaing e-mail/phone records from reporters and from members of Congress, goes beyond what Richard Nixon did with his "enemies list." S.B. Hood River, OR

A: Well, Nixon wanted to use the IRS to audit his enemies, and the NSF to deny them grant funding, and the DoJ to hit them with lawsuits, and other abuses like that. We're not sure if those are better or worse than going after someone's personal communications. However, Nixon's underlings refused to play ball, and so his plans never came to fruition. Trump's underlings, by contrast, said "Yes, sir, and is there anything else unethical that I can do?" So, we would say Pelosi is right, on that basis.

Q: You wrote that "[the Republicans'] base (at least, much of it) hates Obamacare." Is there polling data that confirms this? Has no one from their base signed up for health care through the ACA exchange? Did the votes for Medicare expansion in red states, such as Idaho and Utah, somehow not include the GOP base? Is this a case of people benefiting from Obamacare but not realizing it? I recall some number of years ago seeing an Obamacare protest where a person was holding a sign that unironically said something like, "No socialism! No government takeover of my Medicare!" R.L., Alameda, CA

A: There are lots and lots and lots of polls. See here for some charts that aggregate the data, and make clear that Obamacare is very unpopular with a large swath of the Republican Party. On top of that, a few years ago, there was a subgenre of newspaper articles that involved interviews with people who got insurance through Obamacare, and yet proudly declared how much they hated the program.

Some of the opposition is due to legitimate complaints about the program. Some of it is reflexive opposition to any expansion of government power. But some of it, well...polls consistently show that "The Affordable Care Act" is more popular with voters (and with Republicans) than "Obamacare," despite them being the exact same thing. Clearly, at least some of the opposition to Obamacare is hatred for anything done by "the libs," in general, or Barack Obama, in particular.

Q: Please help me to understand. When Donald Trump was president, there were several pieces of legislation he couldn't pass due to him not having enough votes in the Senate. Republican Senate leadership, though under much pressure, refused to invoke the nuclear option and remove the filibuster. If I'm recalling this correctly, it appears that despite pressure to get rid of the filibuster, Democrats and Republicans realize doing so would be a terrible mistake in the long run. T.A.C., Baltimore, MD

A: There are clearly some senators who believe that it's important for the minority party to have some means for making their voice heard. There are undoubtedly even more senators who are thinking about their personal needs as a member of the minority (either right now, or in the future).

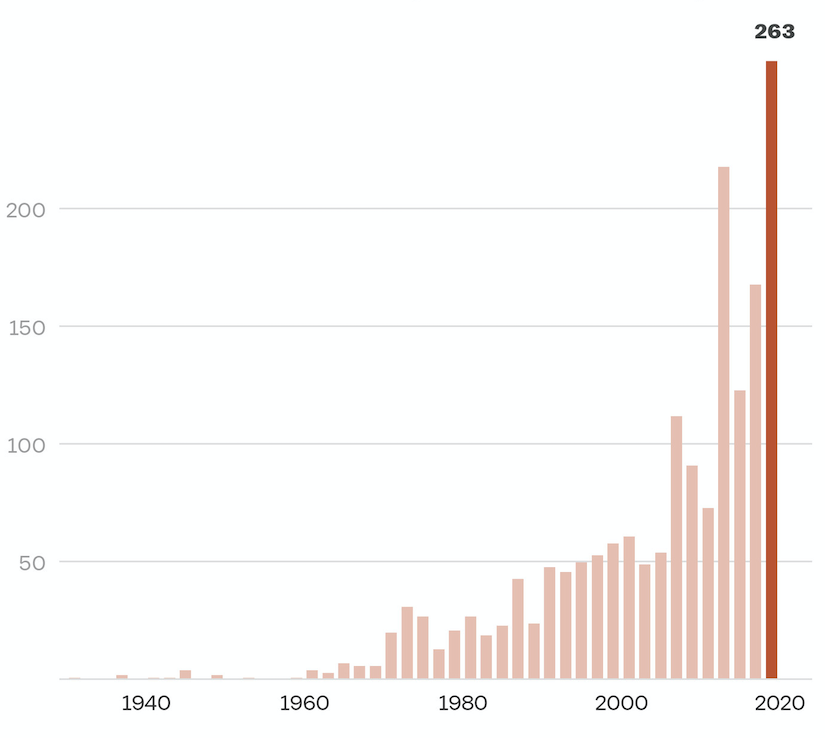

The question is: At what point does the filibuster become abusive? There isn't actually a way to track filibusters, per se, but a pretty good proxy is cloture votes, which are used to try to end filibusters. Here's a chart of how many cloture votes the Senate has taken in each term since the FDR years:

As you can see, cloture votes (and, by extension, filibusters) have become vastly more common in the last decade or so, with there being a clear spike at the time that Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) moved into the Senate leadership (2007). Further, Republicans filibuster approximately 40% more than Democrats do. Is this enough to say the system is broken? That could be the $6 trillion question, if Joe Biden gets his way.

Q: In many of the articles regarding possible filibuster reform, you mention "reading the Alabama phone book." Texas has a talking filibuster, as demonstrated a few years ago by Wendy Davis. One of the rules of the filibuster is that the discussion must be relevant to the bill under consideration, which in my opinion is one of the few common-sense provisions of the Texas Legislature. Is there a reason this is never mentioned as a possibility for the U.S. Senate? S.F., Hutto, TX

A: It is sometimes mentioned, but enforcement could be tricky. What if a Senator, while filibustering, said: "I am concerned that the For the People Act will harm many of my constituents. Let me read you the names of some of the people that might be harmed..." and then launched into a run through the phone book? Clearly a stalling maneuver, but also arguably relevant to the matter at hand. Presumably, the judgment would have to be put into the hands of the Senate parliamentarian and her deputies, but they may not be thrilled to be put on the spot like that.

Q:

Headline

from The Washington Post: "Biden finds himself caught in politics of Catholic Church."

Joe Biden is arguably the most observant U.S. president in decades and the nation's most prominent Catholic politician.

He rarely misses Mass, he quotes scripture, and his faith has long been a core part of his identity. He's also a

liberal, and that's stirring up the U.S. Catholic bishops fighting cultural battles within the church.

I don't get it. I have a master's degree from what would be considered an evangelical Christian seminary. I have

followed politics closely my entire adult life (which is now approaching its expiration date). What I don't get is: How

did the issue of abortion become the be-all and the end-all of morality for large swaths of American Christians, the

issue that trumps or obliterates all other issues? Early this year I renewed friendship with a friend from seminary. I

discovered that for the last 40 years he has only voted Republican and that he is, by his own description, a "one-issue

voter." Given the scope of the Bible and given the age of Christianity, and its roots in Judaism going back much

further, how did so many American Christians conclude that there is only one issue that matters? Not just one moral

issue, but only one issue. I don't get it.

Also, for four decades I taught history—US, European, Chinese, ancient, so I'm used to explaining things, seeing

their roots, unraveling the complexities of a problem and its development. I still can't grasp how this one issue

become the one and only issue. I write this because I have been confronted with the fact that many people think

this way; it's not my impression: They told me so.

Help me, Obi-Wan—ok, (Z) and (V)—you're my only hope.

B.C., Walpole, ME

A: There are a number of things that, if we were church leadership, and were searching for an issue to rally parishioners around, would make opposition to abortion a good choice:

- If one believes that a fetus is an infant, infants/children engender strong emotions and much sympathy

- Abortion lends itself to a binary, "I'm for it or I'm against it" approach, which is not true of other, less

black-and-white issues, like "is it really important that people not eat meat on Fridays?"

- It's a pragmatic bit of scripture to rally people around. Divorce used to be a big one, but that is not viable

today. And some stuff, like most of Leviticus (no more cheeseburgers or shrimp cocktails), would never fly.

- It affects only women, and the Catholic Church, along with many other Christian churches, just so happens to be run entirely by men.

These are general reasons why abortion might be a viable wedge issue. There are specific reasons why it did become a wedge issue in the 1970s:

- The modern feminist movement emerged, and bodily autonomy was one of their key concerns, leading 20 states to

establish protections for at least some forms of abortion (which was previously illegal nationwide)

- Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, making abortion legal nationwide, and upsetting the status quo of

"Democratic-controlled states tolerated it and Republican-controlled states did not."

- The religious right, as embodied in organizations like the Moral Majority, decided that they wanted to be a political force. Abortion was both a religious issue and, because of feminists and their Democratic supporters, a political one. Some issues are political but not really religious (say, how to wage the Cold War) and some are religious but not really political (say, whether or not to speak Latin in church). That said, as the religious right has gotten more established and comfortable in the political arena, they've gotten much more comfortable making all political issues religious, and all religious issues political.

Q: You wrote: "Biden would probably have to agree to return a few Russian convicts to Putin." I know prisoner exchanges happen all the time, but how does this exactly work in a democracy? Can the executive (or even the legislature) simply cancel a conviction made by the justice system? H.M., Berlin, Germany

A: The type of people Putin wants back would be federal prisoners convicted of federal crimes. And that being the case, the President can indeed commute their sentences or pardon them entirely.

Q: In your item "Supreme Court News, Part I: The Calm Before the Storm," you mentioned Biden v. Sierra Club. I understand that this lawsuit was started while Donald Trump was still president. Is there a legal, political, financial, or other reason that Biden cannot simply 'admit defeat' and settle? I'm not sure why the Biden administration would want to defend the Trump administration's spending on a wall that Biden doesn't want. S.J.P., Clarksville, TN

A: The Biden administration does not want to defend the case, which they made clear in the brief that the acting solicitor general filed with the Court last week. However, they really don't want SCOTUS to issue a broad ruling that prohibits all redirecting of funds by a president. What Team Biden wants is a ruling that merely prohibits this particular redirection of funds by a president. So, the briefing actually asks the Supreme Court to vacate the existing rulings on the case, and to kick it back down the ladder, so a lower court can issue a narrow ruling on the facts of the case as they currently stand.

Q: You

wrote:

"Voters may say they want bipartisanship but it's like balancing the budget or reducing the national debt—it sounds

good, but people don't actually back that position with their ballots."

In that case, what would you suggest for someone who's been very concerned for over a decade about balancing the budget

and reducing the national debt? Because based on their actions over the last 20 years, it seems

like neither major party actually cares enough to do anything about it, regardless of what they might say. Is the only

hope a divided government like we had in the late 90s? Or a third party like the Libertarians (who specifically address

this in their official platform; I've backed them before but they never seem to get any traction)?

P.T., Parsippany, NJ

A: If neither of the major parties takes an issue seriously, and only pays lip service to that issue, you are indeed kinda out of luck. The only thing we can suggest is to look for outcomes that have, as a byproduct, a healthier budget picture, and back the party that seems to be better at achieving those outcomes. Put another way, the deficit and the budget are less grim when the economy is booming. So, which party seems to do better on the prosperity front?

Q: If someone wants to support various causes like combating global warming, racial justice, voter rights, plastics in the oceans, etc., do you think it is more effective to support particular groups or to support the Democratic Party in terms of time and money? This is particularly relevant to people who have limited quantities of those things. D.K., Iowa City, IA

A: If you have one issue you rank above all others, then you should probably support an organization dedicated to that issue. But if you care about all of these issues roughly equally, then you should probably give most of your time and money to the Democrats, since they are in a position to implement policy, whereas NGOs largely are not.

Q: I had a question about antebellum manumission. And by "antebellum," I mean before the American Revolution. I'm a big fan of the series "Outlander." There's a scene (in season 4, episode 2, "Do No Harm"), where the main character, Jamie, is offered a pre-revolutionary plantation as an inheritance in North Carolina, including all of the slaves. His wife, who is from the 20th century, is appalled at the idea of owning slaves and Jamie is not keen on the idea either. They suggest freeing the slaves (or perhaps even paying them), but the local pooh-bahs explain to him that it's a very bad idea, enumerating numerous legal and practical obstacles. I'm sure the requirements varied from state to state and from one time period to the next, but I do get the feeling that manumission wasn't just a matter of signing a slip of paper, declaring Eliza was free, and off she went. Could you elaborate a bit on this? F.L., Denton, TX

A: This is correct. Free, Black Southerners were a threat to the social order, since they might plausibly encourage slaves to run away or rebel, or they might ally with poor whites and rebel against rich whites. So, the Southern states passed a lot of laws that made it difficult-to-impossible to manumit those who were enslaved.

Another complication was that the "owners" of slaves often did not have clear legal title to their chattel, usually because they were inherited as part of a trust or other legal arrangement, or they were part of a dowry/marriage contract. For example, George Washington wanted to free most or all of his slave laborers in his will, but the majority of them legally belonged to Martha and not him, and were only bound to him while they were married (which they were not, anymore, the moment he died).

Q: I am loving the alternate history questions and your responses to them! Here's a real humdinger: Was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln perhaps the greatest blow to racial equality the U.S. ever suffered, given its timing and who replaced him? O.Z.H., Dubai, UAE

A: The greatest blow to racial equality is undoubtedly some key event that established race-based slavery as an element of American society, or that assured its continued viability. The event that occurs to us is the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, which saved the Southern slave economy, and was surely more impactful than Lincoln's death.

If Lincoln had lived, then Reconstruction would certainly have been less rocky than it actually was. However, despite his immense political skills, as well as the enormous political capital he had by virtue of winning the Civil War, it is very hard to see how he might have changed the course of American race relations all that much. Southern society was fundamentally built on white supremacy. Further, it wasn't until the 1890s, by which time Lincoln would not only have been out of office but also dead, that American apartheid really resumed.

Well, ok, there is one thing he might have done. If he had embraced some version of "40 acres and a mule," and had turned the freedmen into small, independent business owners—rather than vassals who remained tied to the land (and to their former masters) via sharecropping—that might have changed the calculus. But he was personally uncomfortable with that sort of trampling on property rights, and even he would have struggled mightily to sell it to a majority of Congress. Recall that they barely agreed to end slavery, clearing the two-thirds hurdle for the Thirteenth Amendment by just two votes. Giving the freedmen and women a bunch of land, and land taken from white people no less, would likely have been a bridge too far.

Q: Here's another alternate history question for the resident Civil War historian: How would the latter part of the 19th century have played out differently if Hannibal Hamlin had not been replaced by Andrew Johnson as Lincoln's running mate in the 1864 election? A.J., Baltimore, MD

A: The 19th century? Probably not very different than it actually did. As we note in the previous answer, transforming the South was likely beyond even so great a politician as Abraham Lincoln. So it was certainly beyond the power of Hamlin.

The 20th century, on the other hand? It might well have been much worse than it actually was. Hamlin was a much more competent politician than Andrew Johnson, and was considerably less racist. This being the case, he would have gotten along with Congress, and in particular the moderate wing of the Republican Party, much better than Johnson did. However, Johnson's bad behavior was what drove the moderates into the radical camp, and so allowed for the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. With Hamlin, there's no impeachment, but there's probably no amendments either, beyond the Thirteenth. And can you imagine how much tougher a hill it would have been to climb if Black Americans entered the 20th century and, in particular, the mid-20th century, without laws already on the books that required they receive equal treatment before the law, and also that they be given the right to vote?

Q: You

wrote:

"And while it is true that wars exact a terrible toll in terms of blood and treasure, they also

tend to dramatically hasten scientific progress, cultural change, economic modernization, and other forms of growth."

I'm wondering if you see any good having come out of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars?

B.B., Panama City Beach, FL

A: Nope. Vietnam was a pretty awful war, and yet we can still make a case that it had a few positive outcomes, most obviously persuading the U.S. to change its approach to the Cold War without an even bigger loss of blood (or without things getting nuclear). But we just can't make a case for Afganistan and Iraq.

If you wish to contact us, please use one of these addresses. For the first two, please include your initials and city.

- questions@electoral-vote.com For questions about politics, civics, history, etc. to be answered on a Saturday

- comments@electoral-vote.com For "letters to the editor" for possible publication on a Sunday

- corrections@electoral-vote.com To tell us about typos or factual errors we should fix

- items@electoral-vote.com For general suggestions, ideas, etc.

To download a poster about the site to hang up, please click here.

Email a link to a friend or share:

---The Votemaster and Zenger

Jun18 McConnell Promptly Shuts Manchin Down

Jun18 American Racism, Past and Present

Jun18 Keeping Trumpism Alive, Part I: Immigration

Jun18 Keeping Trumpism Alive, Part II: Trump for Speaker

Jun17 Biden and Putin Met and Nothing Happened

Jun17 Manchin Is Open to a Mini-H.R. 1 Bill

Jun17 Schumer Is Following Two Paths on Infrastructure at the Same Time

Jun17 DSCC Will Spend $10 Million to Protect the Vote

Jun17 Mayors Have Had It

Jun17 Trump Is Struggling to Clear the Field in Senate Primaries

Jun17 Dept. of Justice Will Focus on Domestic Terrorism

Jun17 Biden Will Double Number of Black Women on Appeals Courts

Jun16 Bipartisan Bill Has One Foot in the Grave (and the Other on a Banana Peel)

Jun16 1/6 Realities Diverge in Congress

Jun16 Surprise! White House Pressured DoJ to Help Overturn Election

Jun16 Many Things Are Coming Up Roses for Progressives

Jun16 There's Good News and There's Bad News on the COVID-19 Front

Jun16 Florida Does an End Run around the Rules

Jun16 Kushner Signs Book Deal

Jun15 VP I Is Going to Be a Tougher Challenge than QE II Was

Jun15 Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal Is in Trouble

Jun15 Supreme Court News, Part I: The Calm Before the Storm

Jun15 Supreme Court News, Part II: McConnell Admits What Everyone Already Knew

Jun15 This Week's 2022 Candidacy News

Jun15 Virginia Governor's Race Could Be a Barnburner

Jun15 Adams Looks to Be in the Catbird Seat

Jun14 Biden Doesn't Stomp Out of G7 Meeting

Jun14 McConnell Tries to Exploit Biden's Weakness

Jun14 Collins Clarifies How the Gang of 10 Will and Will Not Pay for Its Infrastructure Bill

Jun14 The States Are Proving Manchin Wrong

Jun14 Justice Dept. Is Going to Look at Barr's Spying on Democrats...and Republicans

Jun14 Nevada Is Helping Iowa Stay First

Jun14 Republicans Are Complaining about 2024 Debates Already

Jun14 Israeli Parliament Approves New Government

Jun13 Sunday Mailbag

Jun12 Saturday Q&A

Jun11 We Have a Deal...Or Maybe Not

Jun11 FBI Is Not Investigating Trump's Role in Insurrection

Jun11 Senate Confirms First-Ever Muslim Judge

Jun11 Omar Ruffles More Feathers

Jun11 Sinema, Boebert May Be Playing with Fire

Jun11 A Possible Answer to the Manchin Mystery

Jun11 Dumbest Member of Congress Unwisely Opens His Mouth

Jun11 California Democrats Move the Goalposts a Bit

Jun11 About Those Vaccine Incentives...

Jun10 Biden Goes to Europe

Jun10 Gang of 10 Wants to Do Infrastructure without Raising Taxes

Jun10 Democrats Can't Figure Out What Manchin Wants

Jun10 Transcript of McGahn Hearing Is Released